Publications IPH Magazine Revista IPH Nº17 Natural ventilation for hospitalization environments: historical aspects

- IPH Magazine #17

- COVID-19 pandemic and the trends in healthcare design: insights from the "Decalogue for Resilient Hospitals"

- Healthcare closer to people: A qualitative study of a Swedish reform on healthcare delivery

- Spatial flexibility and extensibility in hospitals designed by João Filgueiras Lima

- Design Insights from a Research Initiative on Ambulatory Surgery Operating Rooms in the U.S.

- A study on the development of the concept growth and change on hospital architecture in Japan

- A study on hospital infection control through architecture in 1980: Chapecó Regional Hospital case study

- Natural ventilation for hospitalization environments: historical aspects

- Hospital architecture and its propositions for beginners and experts

Natural ventilation for hospitalization environments: historical aspects

Kátia Maria Macedo Sabino Fugazza - UFRJ, Brazil

ABSTRACT

This article derives from the master's thesis presented in 2020, entitled "The Path of the Winds: The Perception of Natural Ventilation in Hospitalization Environments" presented to the Post-graduation Program in Architecture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. This work focuses on the historical background of healthcare environments with an emphasis on natural ventilation to thus evaluate the changes throughout the process of admitting users.

KEYWORDS: Hospital architecture, Natural ventilation, Environmental comfort.

INTRODUCTION

This article derives from the master's thesis presented in 2020, entitled "The Path of the Winds: The Perception of Natural Ventilation in Hospitalization Environments" presented to the Post-graduation Program in Architecture at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in which we mapped the historical panorama of natural ventilation within healthcare environments and the current perception of users during the hospitalization process. Two hospitals were chosen as case studies to obtain the results: Gaffrée and Guinle University Hospital (HUGG) and Lourenço Jorge Municipal Hospital (HMLJ). The methodology used to obtain the results included computer simulations, interviews and hygrothermal measurements. The present work addresses the historical background of healthcare environments with an emphasis on natural ventilation to evaluate the changes that have occurred during the process of admitting users.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF NATURAL VENTILATION WITHIN HEALTHCARE FACILITIES

The first healing environments came around in ancient Greece and Rome. Mainly in temples, such as Asclepius', God of Medicine. Those were sacred environments that believed rest and treatment of diseases should be done through purifications and dreams. In practice, a healthy and pleasant space where patients waited for divine healing. Its spatial configuration was linear, composed of three blind façades, frontal opening, and Greek columns (THOMPSON and GOLDIN, 1975) (Illustration 1).

Illustration 1 - Double nurse station floor plan in the Temple of Asclepius, 5th century BC

Source: Thompson and Goldin (1975).

Back then the idea of health was related to the balance of moods in the body, and it comes from this period the collection of medical treatises called Hippocratic Corpus, from the second half of the 5th century BC, which relates the temperature of the winds of a city to the diseases of its people and their customs (Cairus, 2005), and On the Winds - Gases, which mentions specifically the air as a means of cure or disease from the last quarter of the 5th century BC (REBOLLO, 2006) . They believed diseases were caused by unhealthy miasmas and air was the source of life (DELGADO, 2008).

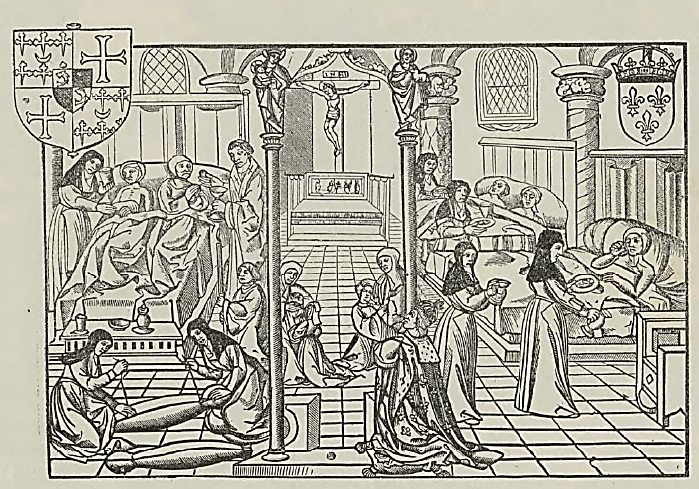

This concept lasted until the Middle Ages in Europe, where infectious diseases, charity and salvation were seen as one thing (Rosen, 1979). The soul and the body were unique, and the diseases, suffering and poverty were God's design.

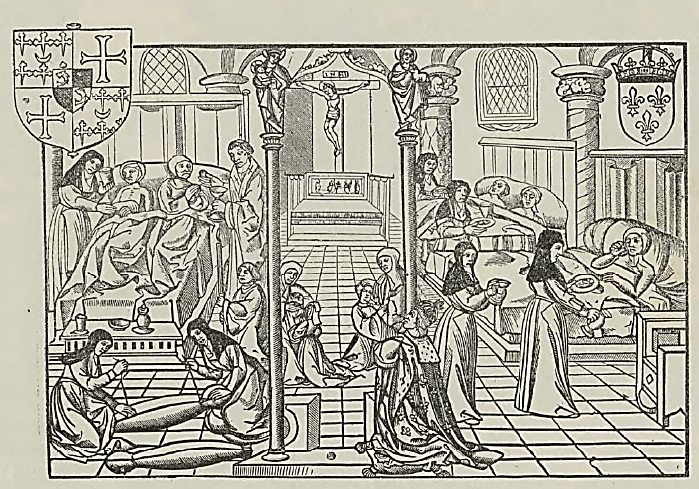

Following this proposition, the first hospitals appear. Its purpose was to receive anyone who needed shelter, comfort, or treatment. And it was within this context that Paris' Hôtel-Dieu appears. With four floors and long wards, it was normal to accommodate up to six individuals in each bed as seen in Illustration 2, without any natural ventilation system within the building (TENON, 1996).

Illustration 2 - Hôtel-Dieu hospitalization environment.

Source: Tollet (1892).

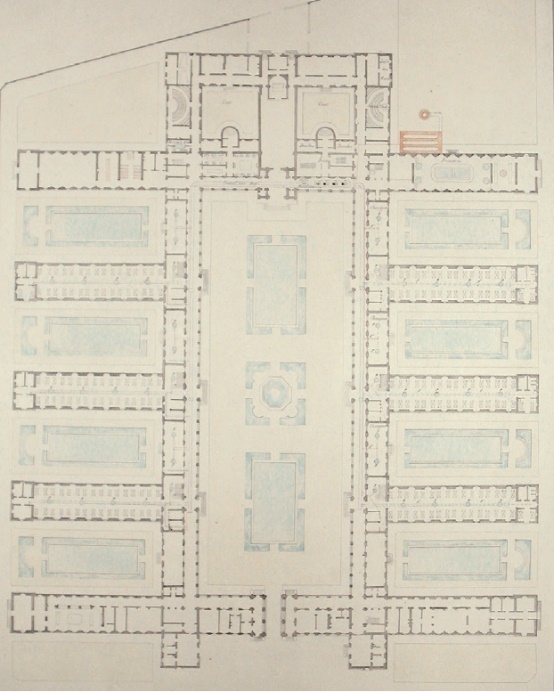

In the 15th century the concern regarding natural ventilation within hospitals resumes and, in 1456, the Ospedale Maggiore is designed for the city of Milan. The design consisted of nurse stations connected through doors towards an outdoor backyard (THOMPSON e GOLDIN, 1975). It is considered until today the best typology by the World Health Organization (2009). It was also used to air renovation and chimney climatization, therefore exiting the air through pressure (Illustration 3).

Source 3 - Ospedale Maggiore corridors, in Milan, 1504.

Source: Thompson and Goldin (1975).

Due to population growth, epidemics, cemeteries, and sewage in the middle of the city, the miasma theory resurfaces in the 18th century and correlates the emergence of diseases to air contamination (ROSEN, 1979). With the purpose of purifying urban environments, the sick, crazy and criminal were taken to isolated areas (ROSEN, 1979).

In this period, research for the revocation of the hospital's harmful effects occurred in order to avoid the contamination of the city's population and to maintain the economic and social order in its surroundings (FOUCAULT, 2018).

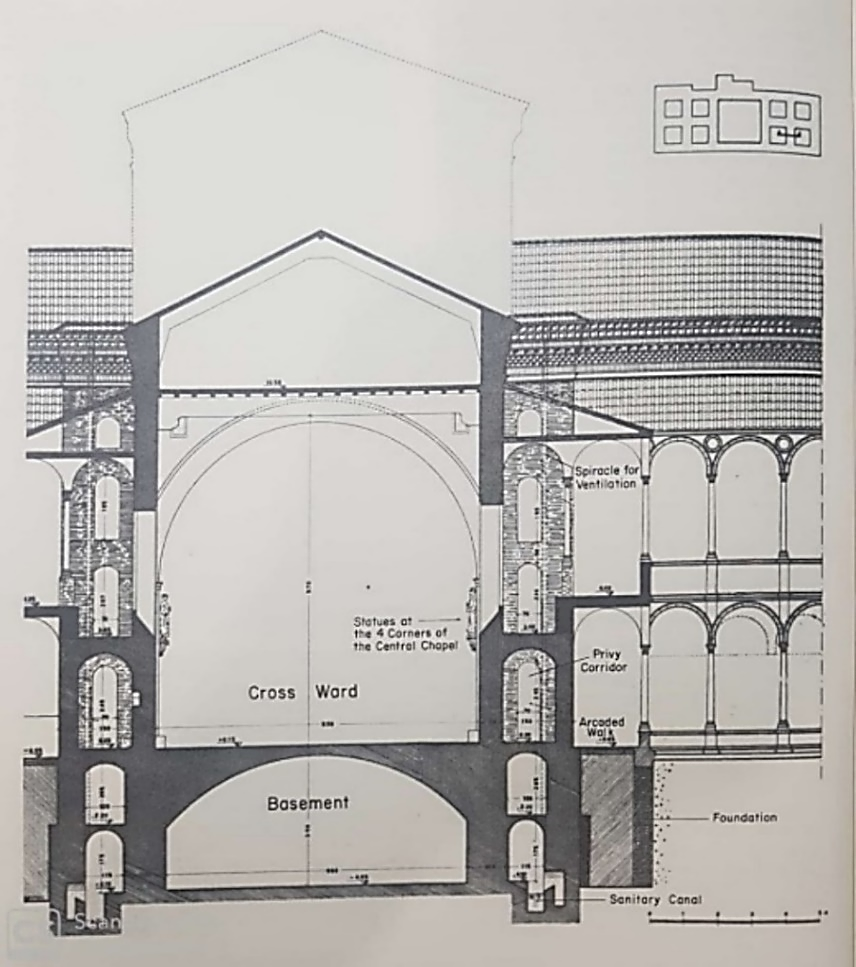

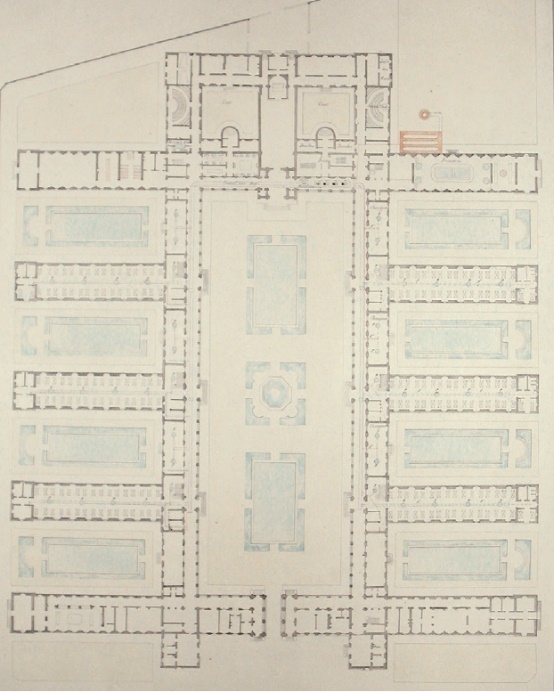

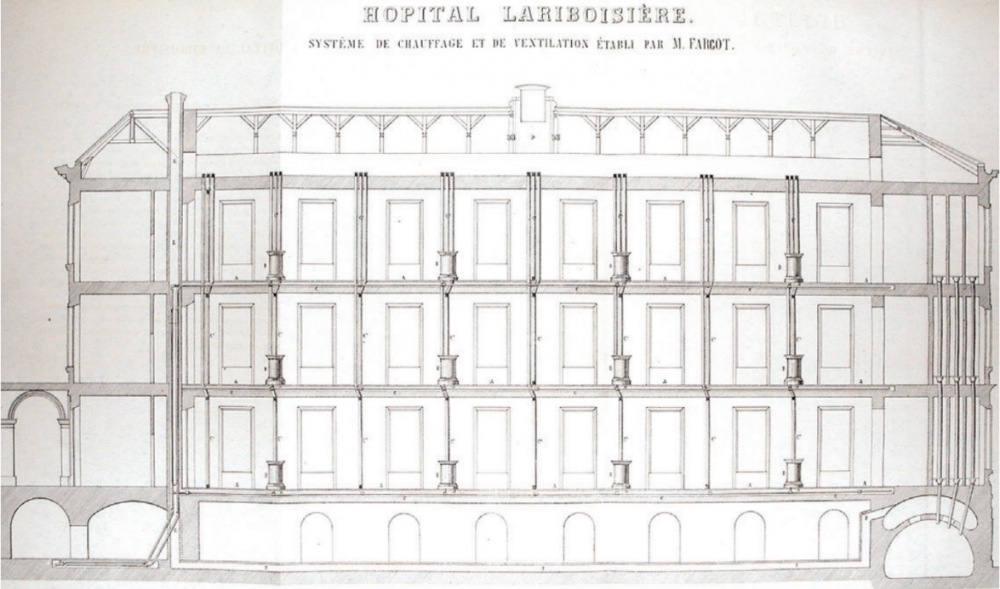

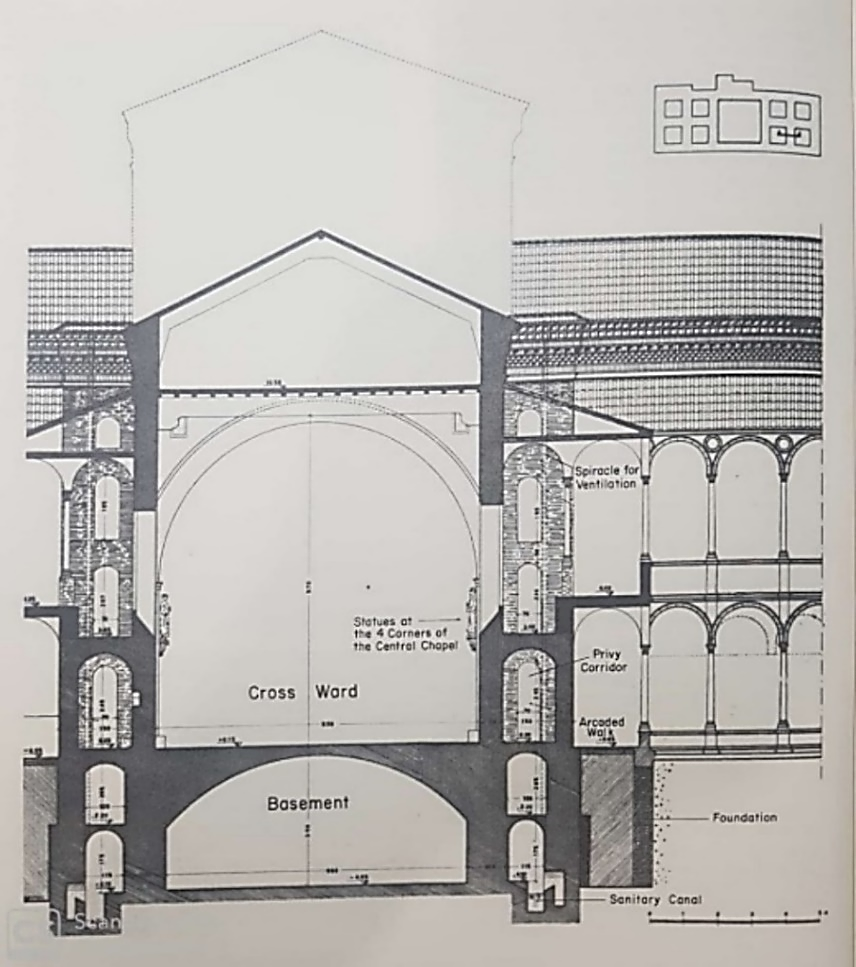

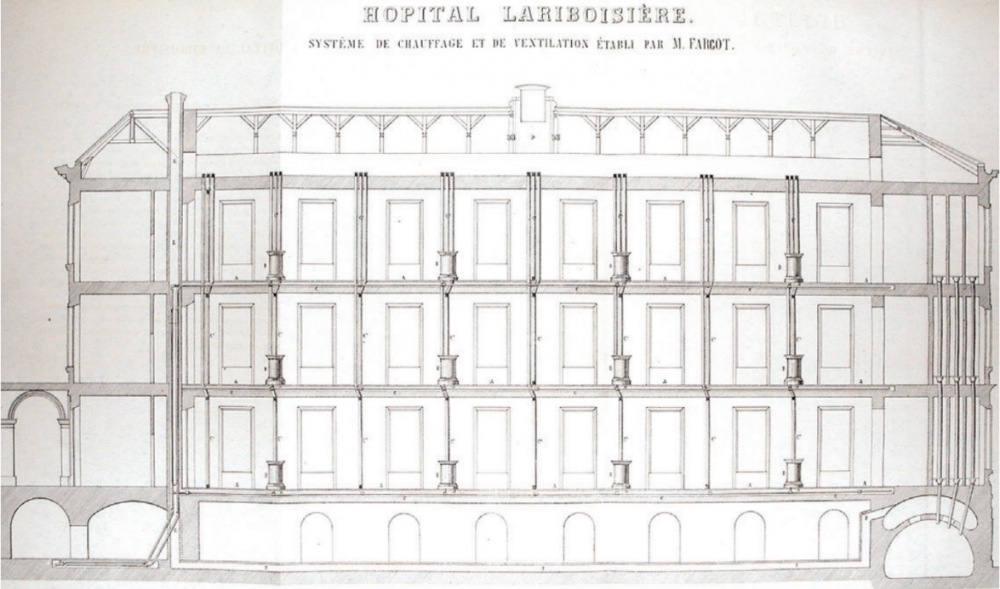

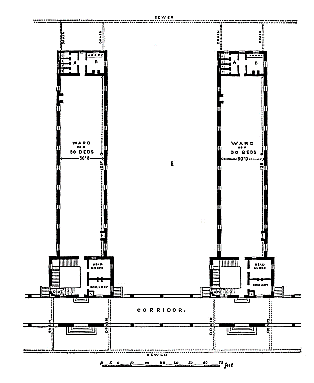

Along with these changes and the collapse of existing hospitals, Jacques-René Tenon, after successive visits to hospital environments, defines the connections between the number of patients, beds, floor area, as well as the height, width and length of environments and air cubage (FOUCAULT, 2018). In 1846, following Tenon's recommendations, the Laribosière hospital was designed, including high ceiling height to achieve the necessary volume for air renovation. The hospital was composed of five blocks and three floors, separated by courtyards with indoor gardens and connected by a wide corridor with two longitudinal axes (THOMPSON and GOLDIN, 1975), as shown in the floor plan of Illustration 4. Therefore, it presented a complex ventilation and heating system for its time (GALLO, 2003), as shown in Illustration 5. Its windows were occasionally opened, especially in the morning, renewing the air in the wards, and when necessary the climatization (heating) would come in to renew the air coming through the ducts serving the hospital (NIGHTINGALE, 1858).

Illustration 4 - Lariboisière Hospital floor plan.

Source: (GALLO, 2003). Available at:<https://bit.ly/38JFIWs>. Access: 8/2/2019.

Illustration 5 - Lariboisière Hospital: ventilation and climatization ducts for the environments.

Source: (GALLO, 2003). Available at: <https://bit.ly/38JFIWs> . Access: 8/2/2019.

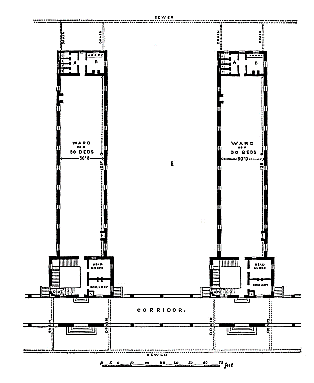

In the 19th century, Florence Nightingale used to see patients as the essence of the hospital. During her volunteering time in the Crimean War, she noticed patients died ten times more from diseases such as typhus, typhoid, cholera and dysentery than from battle wounds. On her return to England, she wrote Notes on Hospitals, in 1859, and Notes on Nursing, in 1860, describing rules and design principles for patient care through ideal nurse stations (Illustration 6).

Illustration 6 - Ideal nurse station according to Nightingale.

Source: Nightingale (1859).

In her writings, she listed methods of introducing fresh air into the ward and claimed that the lack of fresh air was the greatest cause of damage to health during a patient's hospitalization. According to Nightingale, nurses' first attention should be the purity internal air against the external air, to avoid patient deaths. In her books she pointed out the deficiency of space, ventilation, and natural light as a design deficiency in hospitals, and that fresh air, light, amplitude of space and separation of patients in pavilions or buildings would be essential conditions for the wellbeing of users. She also described minimum standards and dimensions for healthcare environments, recommending a reference nurse ward. As in On the Winds (REBOLLO, 2006), Nightingale also stated that fresh air is the source of life (1859).

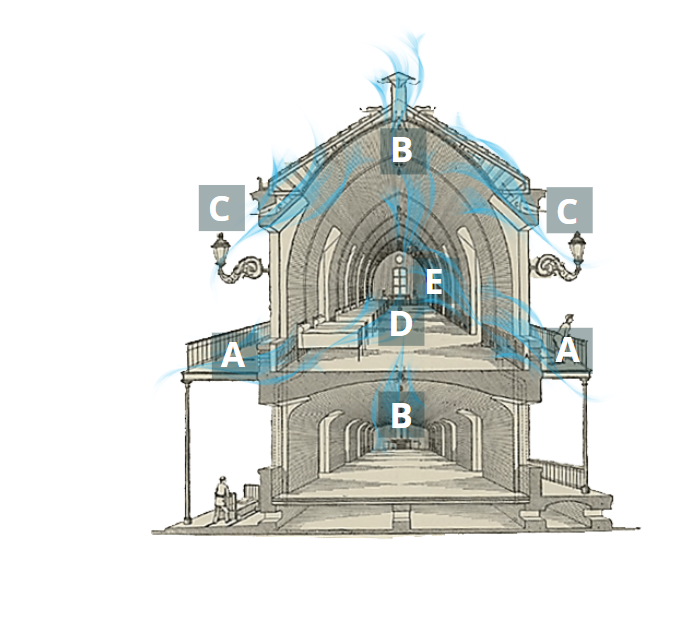

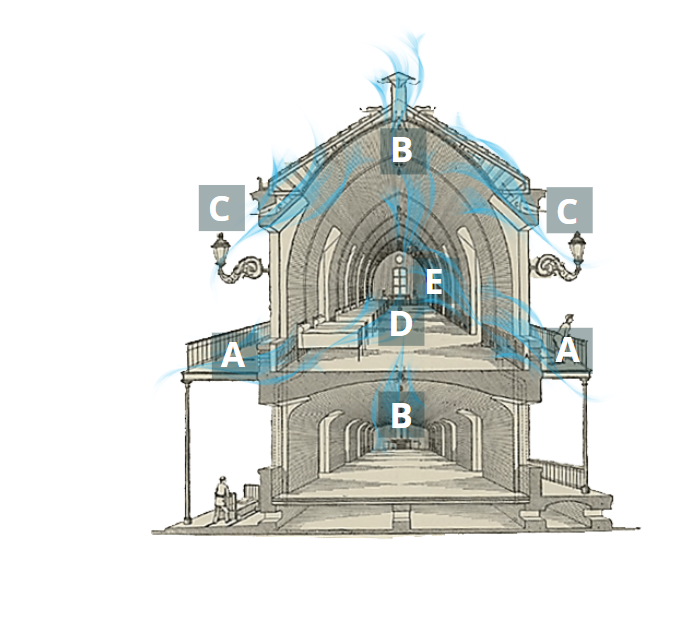

In 1892, Casimir Tollet suggested a new typology for air renewal in nurse wards. Using Gothic architecture, he took inspiration from arched walls to obtain the necessary circulation, thus ensuring the appropriate renewal of 100 l/s/m³ of air per patient, standardized by himself. For Tollet, a ventilation rate of 70 l/s/m³ would be an improvement for the time (1892).

Tollet (1892) designed air entrances through balconies (A), air exits through the ceiling, via a chimney, or through the floor, via lower floor (B), air entrances between the ceiling (C), through the ends of the wards (D) and through fans (E) (figure 7).

Illustration 7 - Tollet's nurse ward for Montpellier Civil and Military Hospital, 1884 - Air circulation in the building.

Source: Tollet (1892) adapted by the author.

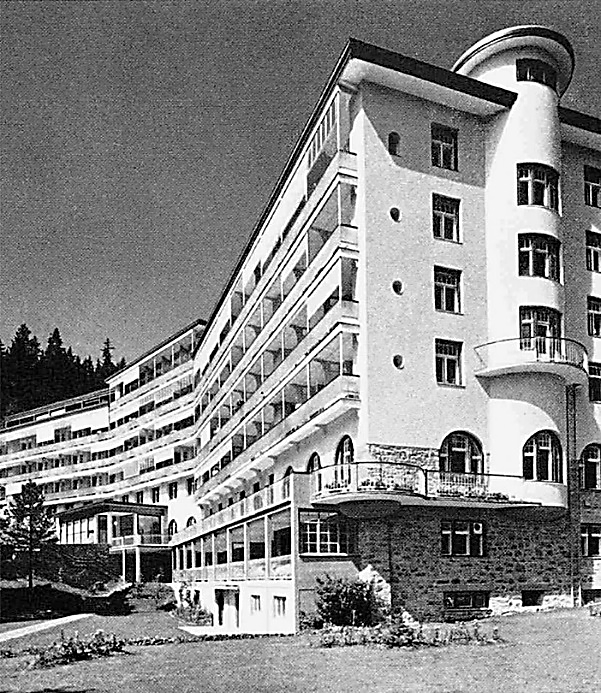

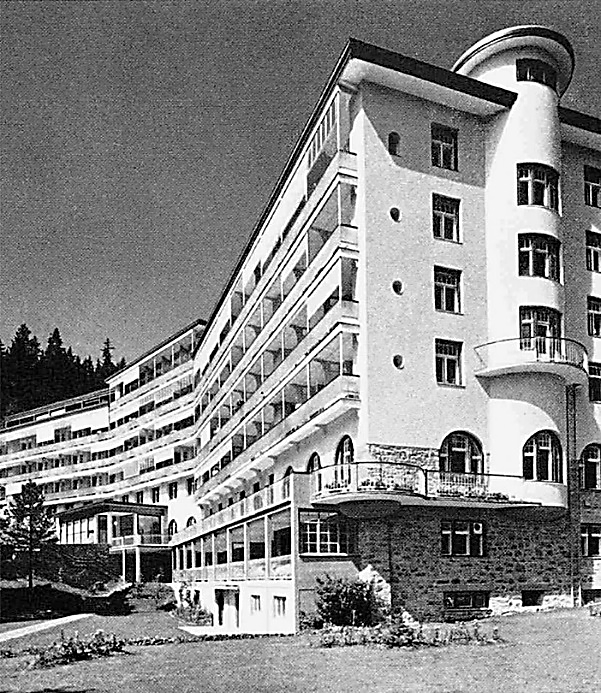

With the emergence of tuberculosis, at the end of the 19th century, sanatoriums were created. Always with large balcony windows, natural ventilation was part of the cure for the disease (BRASILEIRO, 2002). Doctor Spengler, while treating his patients, observed climate and altitude had health-improving properties for patients. For him, mountain air, rest and a good diet would be the cure for diseases. Also, in Davos, Switzerland, a complex climatic spa was created (ASPETAR SPORTS MEDICINE JOURNAL, 2016).

Illustration 8 - Queen Alexandra Sanatorium in Davos Platz, 1906-1909.

Source: Moralez and Diaz (2017).

In parallel with the transformations of the 20th century, the way of getting sick and caring for the sick changed. "Patients change, diseases change, spaces change. Transformations in the process of cognition, attitudes, representations and medical practices have always had some correspondence with changes in the architecture of the hospital space" (SANTOS and BURSZTYN, 2004, p. 146). Charity is left aside, and hospitals become a healing machine (VERDERBER and FINE, 2000). "Changes can also be described (...) as from the passage from pre-antiseptic to the antiseptic period (...) If bacteriology was right, the need for the pavilions was over" (1997, p. 158).

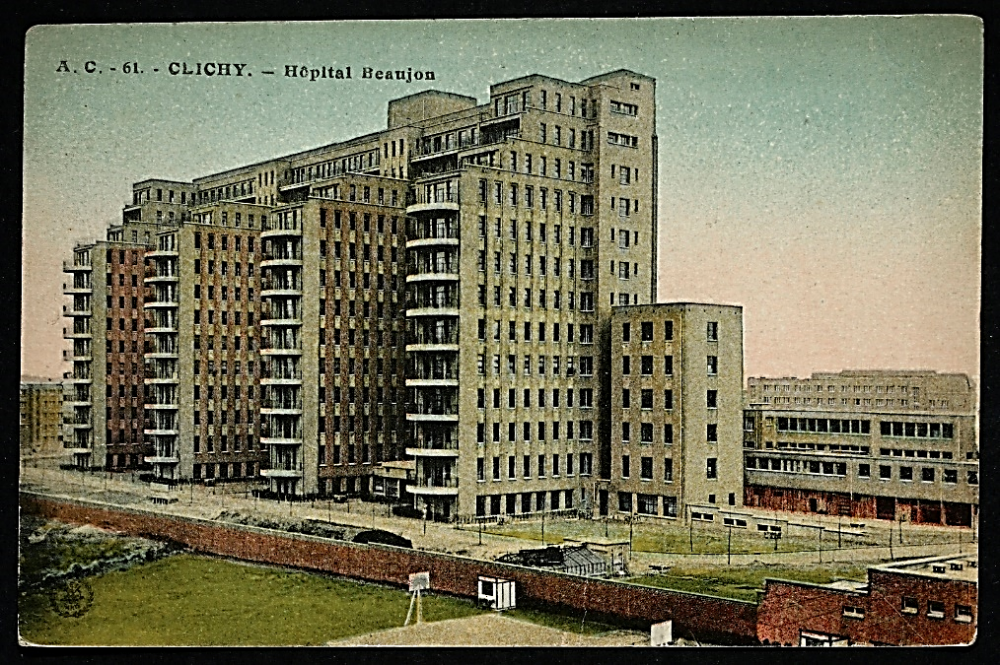

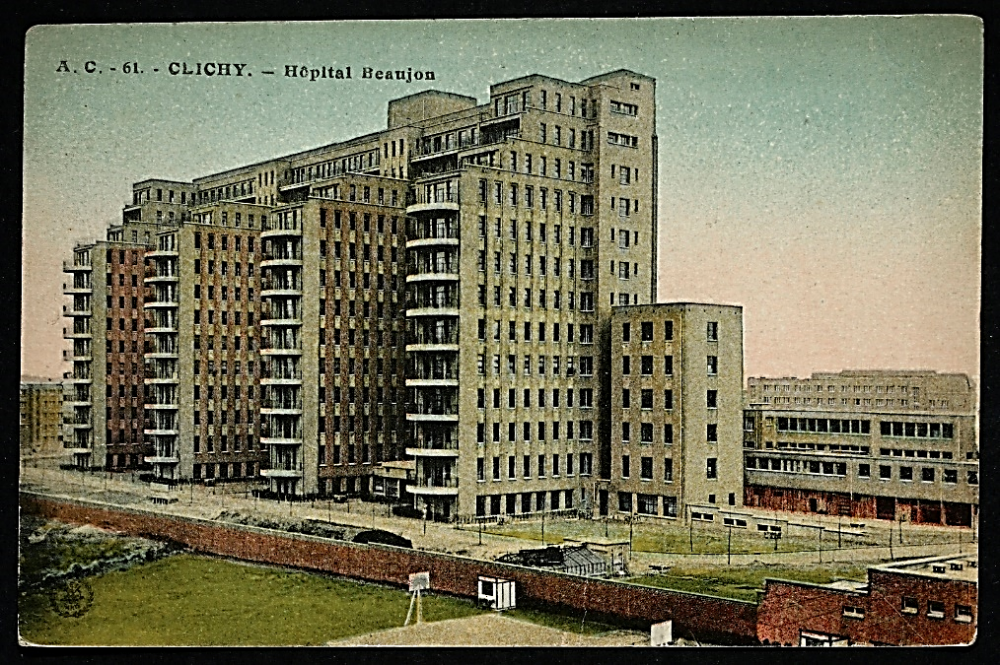

Due to all these advances, the monobloc hospital succeeded, such as the Beaujon Hospital (Illustration 9), exemplified by Verderber (2010) as the most innovative hospital in Europe, with 1,100 beds and built with steel and concrete, its windows were sealed thus giving rise to mechanical air conditioning. The focus is on efficiency and flexibility rather than air and light (KISACK, 2017).

Illustration 9 - Beaujon Hospital, 1932 - 1935.

Source: Geneanet. Available at: http://bit.ly/2Hax846. Access: 11/2/2020.

According to Verderber and Fine (2000), the monobloc hospital typology compacts hospital units, thus facilitating care in the nurse wards. Natural ventilation is no longer a design requirement for health buildings within this typology. At the end of the 21st century, discussions about hospital humanization are already emerging (SANTOS and BURSZTYN, 2004).

Sérgio Bernardes, Jarbas Karman, Domingos Fiorentini, Siegbert Zanettini and João Filgueiras Lima, aka Lelé, pioneered in the use of natural ventilation in health environments. Sérgio Bernardes, in 1951, designed Curicica Sanatorium, in Rio de Janeiro, RJ, currently Raphael de Paula Souza Municipal Hospital for the treatment of tuberculosis. It is organized in a pavilion-like structure and a large green area, its main premises are ventilation and natural lighting (COSTA, PESSOA, et al., 2002) (Illustration 10).

Illustration 10 - Raphael de Paula Souza Municipal Hospital: Outdoor circulation view.

Source: Personal collection (2014).

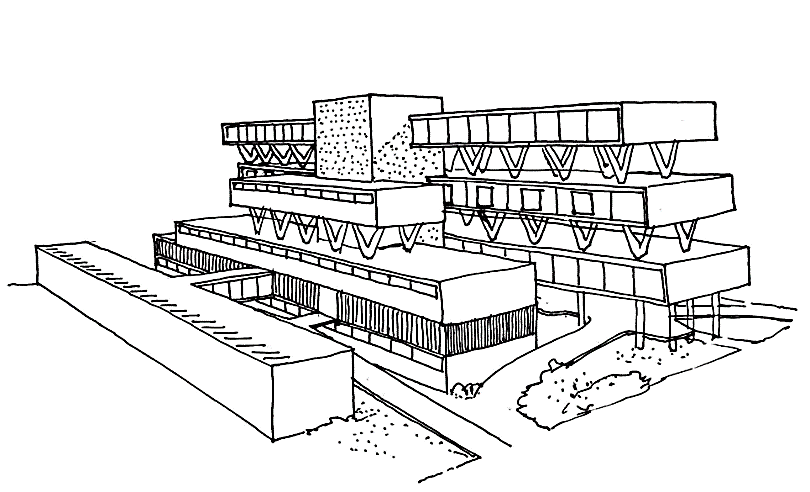

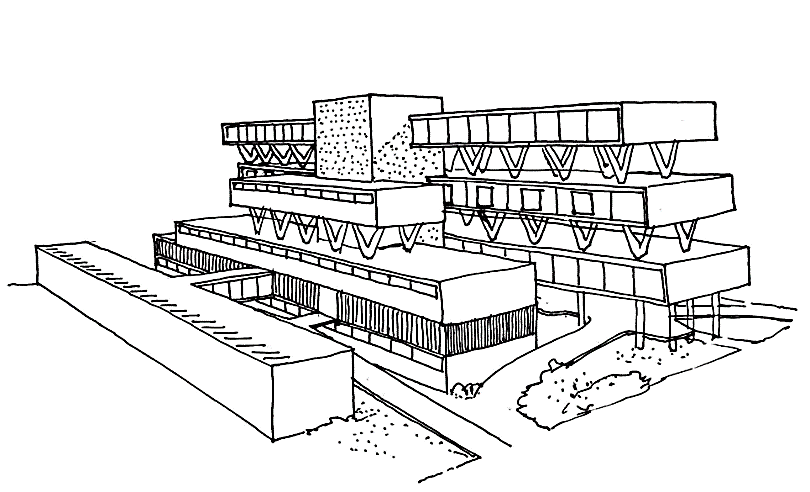

For Hospital das Clínicas in Pelotas - RS (Illustration 11), Jarbas Karman designed voids between the floors in order to allow ventilation and natural lighting indoors. His design was not carried out to the fullest, losing its voids between floors thus leading to a monobloc building (IPH - INSTITUTO DE PESQUISAS JARBAS KARMAN, 2015).

Illustration 11 - Pelotas Hospital das Clínicas.

Source: IPH (2015).

In 1993, architects Jarbas Karman, Jorge Wilheim, and Domingos Fiorentini designed Jozef Fehér building, an expansion for Albert Einstein Hospital in São Paulo - SP, with operable windows that patients have the choice to use to control the best climate for him during hospitalization (MACHRY, 2010).

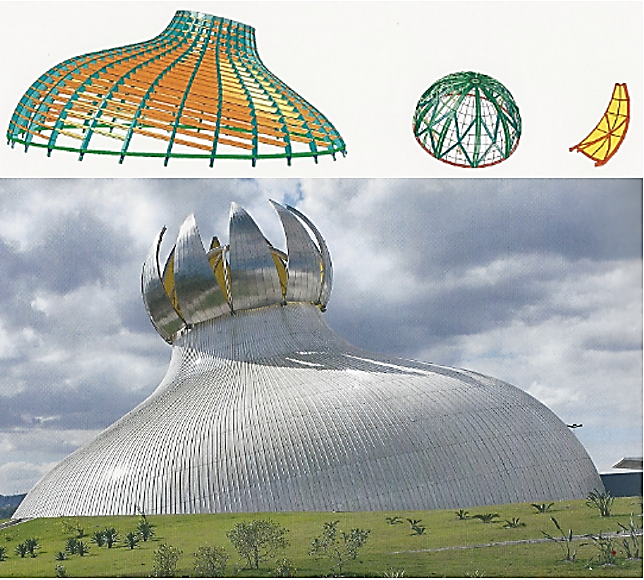

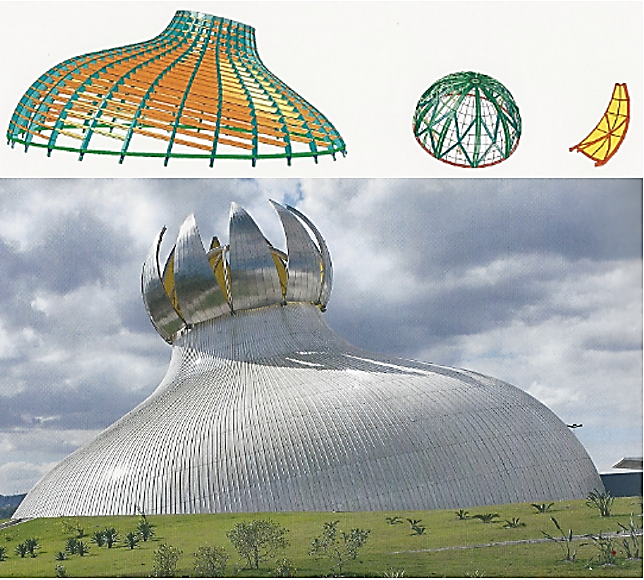

Sarah Group for Rehabilitation Hospitals designed by João Filgueiras Lima focuses on the user, therefore natural ventilation plays an important role for the building. Lima believes that since we live "in the tropics we can only do architecture like this. Otherwise, it is just wrong" (LIMA, 2012, p. 71). In his last hospital, the Rehabilitation Center in Barra da Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, natural ventilation, forced ventilation and air conditioning are used depending on the outside temperature (RISSELDA and RISÉRIO, 2010). For João Filgueiras Lima, the completely "hermetic" health facility (IBIDEM, p. 68) strengthens bacteria, giving rise to hospital infections and "an available technology, which is about to be used" (IBIDEM, p. 68). Illustration 12 shows the auditorium at Sarah Group in Rio de Janeiro which, whenever possible, is opened for air renewal and air conditioning.

Illustration 12 - Auditorium outdoor façade and studies for designing the structure - Sarah Group - Rio de Janeiro.

Source: Risselda and Risério (2010).

CONCLUSIONS

It can be observed that the adoption of natural ventilation in health care environments, despite being renegade and sometimes even despised, has been and continues to be used in healthcare environments as a way to support healing. With the emergence of artificial air conditioning, natural ventilation has been losing ground due to the difficulty in verifying air exchanges or its flow, i.e., the path of the winds. For the best use of natural ventilation, the location of the building, the climate, its surroundings (air quality, noise, among others) and changes in the urban network during the life cycle of the building need to be taken into account since the beginning of the project.

The wind path inside a healthcare building is of vital importance, because too little or too much wind can do more harm than good. Air currents are not welcome, and it is necessary that temperatures and humidity within environments also provide comfort to users. For this, good architecture is of vital importance.

Likewise, not all healthcare environments can use natural ventilation because semi-critical and/or critical environments need strict control of air quality, temperature, and humidity.

The possibility to operate windows becomes a link between external and internal building environments, providing users with the choice to either connect with or block environmental factors. This should be a major factor in the development of the design, especially when it comes to healing environments.

REFERENCES

ASPETAR SPORTS MEDICINE JOURNAL. https://www.aspetar.com/journal/Default.aspx. Aspetar Sports Medicine Journal, 2016. Available at: <https://www.aspetar.com/journal/upload/PDF/2016523102735.pdf>. Acesso em: 22 jun. 2019.

BRASILEIRO, C. D. F. L. Arquitetura antituberculose em Pernambuco: um estudo analítico dos dispensários de tuberculose de Recife (1950-1960) como instrumentos de profilaxia da peste branca. [S.l.]: [s.n.], 2002. Available at: <https://repositorio.ufpe.br/handle/123456789/11138>.

CAIRUS, H. F. 5 - Ares, águas e lugares. In: CAIRUS, H.; RIBEIRO JR., W. Textos hipocráticos o doente, o médico e a doença [online]. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FIOCRUZ, 2005. p. 91-129. Available at: <http://books.scielo.org/id/9n2wg/pdf/cairus-9788575413753-07.pdf>. Access: 5/10/2018.

COSTA, R. D. G.-R. et al. O sanatório de Curicica: Uma obra pouco conhecida de Sérgio Bernardes. Vitruvius, julho 2002. Available at: <https://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/03.026/766>. Access: 11/2/2019.

DELGADO, B. B. Sobre os Ventos: Mito e razão na Grécia antiga através de um tratado hipocrático. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2008. Available at: <http://hdl.handle.net/1843/ECAP-7D3NJ6>. Access: 2019.

FOUCAULT, M. Microfísica do Poder. 7º edição. ed. Rio de Janeiro | São paulo: Paz e Terra, 2018.

GALLO, E. Ventilating and Heating Lariboisière Hospital, a Scientific Debate in Paris 1848-1878 ». poster pour la 3ème conférence internationale pour l'histoire des hôpitaux Form+Function, the Hospital , McGill University, Montréal - Canadá, 19-21 Junho 2003.

IPH - INSTITUTO DE PESQUISA HOSPITALARES JARBAS KARMAN. ACERVO: Projetos Arquitetônicos. IPH - Instituto de Pesquisa Hospitalares Jarbas Karman, 2015. Available at: <http://www.iph.org.br/acervo/projetos-arquitetonicos/hospital-sao-luiz-158>. Access: 09/04/2019.

IPH - INSTITUTO DE PESQUISAS JARBAS KARMAN. O Desenho de Hospitais de Jarbas Karman. 1º Edição. ed. São Paulo: IPH, 2015.

KISACK, J. Quando a ventilação saiu de moda nos hospitais. Instituto de pesquisas Hospitalares Arquiteto Jarbas Karman, n. 14ª edição, 2017. Available at: <http://www.iph.org.br/revista-iph/materia/quando-a-ventilacao-natural-saiu-de-moda-nos-hospitais>. Access: 06/07/ 2018.

LIMA, J. F. Arquitetura: uma experiência na área de saúde / João Filgeiras Lima. São Paulo: Romano Guerra editora, 2012.

MACHRY, H. S. O Impacto dos Avanços da Tecnologia nas Transformações Arquitetônicas dos Edifícios Hospitalares. São Paulo: [s.n.], 2010. Available at: <http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/16/16132/tde-15062010-130613/>.

MORALES, E. J.; DIAZ, I. C. V. Hoteles y sanatorios: influencia de la tuberculosis en la arquitectura del turismo de masas. Hist. cienc. saude-Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro , v. v. 24, p. p. 243-260, Janeiro 2017.

NIGHTINGALE, F. Notes on matters: Health, efficence and hospital administration. London: Harrison and sons, 1858.

NIGHTINGALE, F. Notes on Hospitals. Edição Digital. ed. New York: Dover Publications - Kindle Editions, 1859.

ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DE SAÚDE. Natural Ventilation for Infection Control in Health-Care Settings. Geneva: WHO Library, 2009. Available at: <https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/natural_ventilation.pdf>. Access: 14/06/2018.

PEVSNER, N. A History of Building Types. Priceton: Priceton University Press, 1997.

REBOLLO, R. A. O legado hipocrático e sua fortuna no período greco-romano: de Cós a Galeno. Scientiæ Studia, São Paulo, 2006. 45-82. Available at: <https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1678-31662006000100003>.

RISSELDA, G. L.; RISÉRIO, A. A Arquitetura de Lelé: fábrica e invenção. São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial do Estado de São Paulo: Museu Casa Brasileira, 2010.

ROSEN, G. Da Polícia Médica à Medicina Social. Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal, 1979.

SANTOS, M.; BURSZTYN, I. Introdução: novos caminhos da arquitetura hospitalar. In: SANTOS, M.; BURSZTYN, I. Saúde e arquitetura: caminhos para a humanização dos ambientes hospitalares. Rio de Janeiro: Senac Rio, 2004.

TENON, J. Memoirs on Paris Hospitals. Tradução de Dora B. Wiener. [S.l.]: Watson Publishing International, 1996.

THOMPSON, J. D.; GOLDIN, G. The Hospital: a social and architecture history. London: Tale University, 1975.

TOLLET, C. Les édifices hopitalier: depouis leur origine jusqu'à nos jours. 10º Edição. ed. [S.l.]: [s.n.], 1892. Available at: <http://1886.u-bordeaux-montaigne.fr/items/show/76344>. Access: 15/05/2019.

VERDERBER, S. Innovations in Hospital Architetcure. New York: Routledge, 2010.

VERDERBER, S.; FINE, D. J. Healthcare Architecture: In an Era Radical Transformation. London: Yale University, 2000.

Send by e-mail: