Publications IPH Magazine Revista IPH Nº18 The therapeutic garden

- IPH Magazine Nº18

- The therapeutic garden

- Hospital Sul América and the modern design in health architecture

- RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PLANNING AND CARRYING OUT RENOVATION WORKS IN FUNCTIONAL HOSPITALS

- How spatial syntax can help mitigate the effect of future pandemics in Brazil

- A reflection on the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on architecture and urbanism

- Floor covering of hospital floors: Case study of the vinyl blanket applied in a hospital in Salvador, BA

The therapeutic garden

Moya, Valentina - Cedrés de Bello, Sonia - Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo - Universidade Central da Venezuela

Abstract

This article discusses the effects of gardens on health and satisfaction of users in hospital environments. Based on a literature review, a selection of studies was carried out to highlight the most relevant concepts, and that have contributed to deepen the understanding of therapeutic gardens, presenting some examples of projects that incorporate these concepts and the theories that underpin them. This document is part of a more comprehensive research that aims to identify the implications, benefits, and therapeutic possibilities of the use of gardens in health centers in order to establish concepts of projects to be applied in a case study of nursing homes.

Keywords: therapeutic garden, biophilia, evidence-based design, gardens in health centers.

Introduction

Gardens have been an integral part of hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes and nursing homes that care for the elderly. Thanks to important advances in medicine, technological innovations, economic, social, and cultural changes in care for the population, health facilities have varied their infrastructure, also modifying the design of its outdoor spaces. Nowadays, there is a growing interest of doctors, architects, and researchers in the humanization of health centers, introducing new variables and research focused on rethinking how the design of health center environments influences patient recovery and the well-being of the team. One of the environments that has aroused much interest in this aspect is the introduction of landscaped spaces, both inside and outside hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation centers and residences for the elderly. The concepts of biophilia, evidence-based design and therapeutic gardens stand out among the most used ones in the area of space design intended for health services.

Biophilia

The need of human beings to connect with the nature and be in contact with other animal or plant organisms is called biophilia, word that comes from Greek, bios, life, and philia, love. It literally means "to love life".

The term was defined by Erich Fromm, German psychoanalyst, in "... passionate love for life and the whole living, the desire for growth and development in a person, a vegetable, an idea or a social group" (Fromm, 1973, p. 261).

Later, Edward Osborne Wilson (Wilson,1984), an American biologist, deepens the concept of biophilia and formulates a theory. According to Wilson's theory, people need to have contact with nature, which is critical to psychological development. It states that throughout the millions of years in which Homo sapiens related to its surroundings it has been developed a deep and congenital emotional need to be in close contact with the rest of living beings, plants, or animals. The satisfaction of this vital desire has the same importance as establishing relationships with others. Just as we feel good about socializing, we find peace and refuge when we go to a forest or a beach, look at green walls, or when we are with our pets.

Howard Frumkin (1) (Frumkin, 2017) and Roger Ulrich2 (Ulrich, 2001), among others, referred to E. O.Wilson in their studies and to the theory of biophilia as one of the main ones that support the related benefits between health and nature. Recently, in the field of architecture, the biophilia project is discussed, considered as a sustainable design strategy that seeks to reconnect human beings with their natural surroundings.

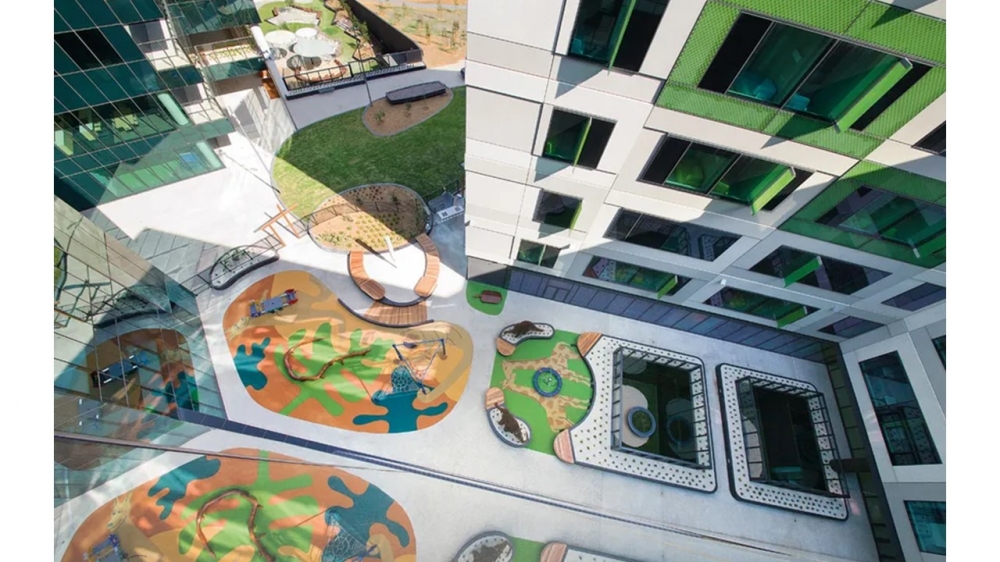

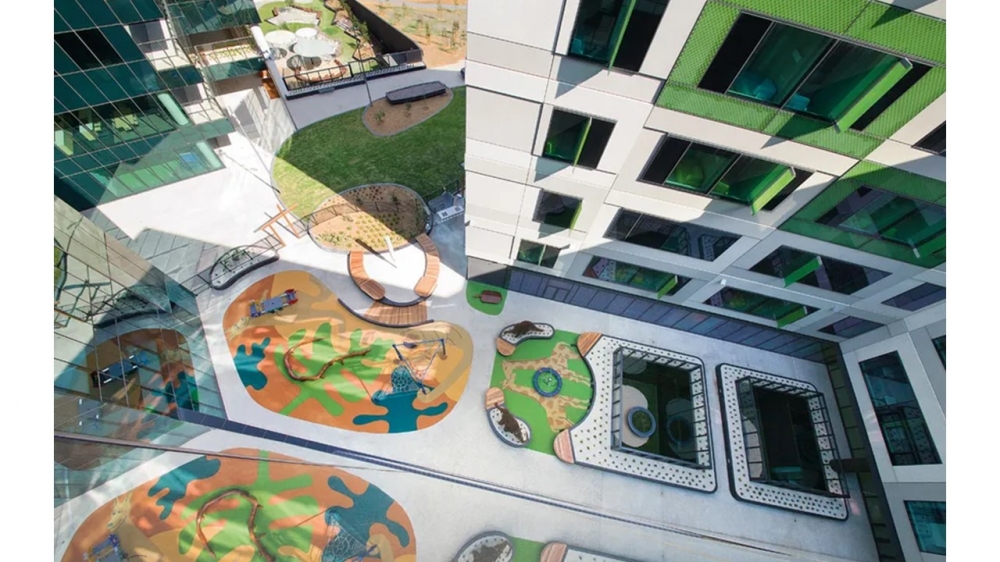

An example of the application of biophilia concept in architecture to improve health of the sick is the Royal Children's Hospital, designed by Billard Leece Partnership and Bates Smart (Bull, 2012), in Melbourne, Australia, located in a green surrounding (Picture 1). Today, it has

become a reference in the provision of health services aimed at children. The principles used were: evidence-based design, family-centered design, sustainable design, introduction of daylight and nature in the work and sanitary surroundings, gathering of clinical, research and education facilities.

(1) Professor of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Washington School of Public Health.

(2) Professor, Department of Architecture and Center of Sanitary Architecture, Chalmers Technological University.

Picture 1: Play space, designed by Fiona Robbe, landscape architect, Royal Children's Hospital. Source: Gollings, Jhon (2012) (Photography). https://architectureau.com/articles/new-royal-childrens-hospital/#

The patient rooms are separated into three areas (clinic, patient, and family), responding to the emotional needs of children. Each child can customize their space (Picture 2), as well as views of the inner courtyards or the Royal Park, which improves patient's experience and recovery rates, which has been proven in different studies. They also ensure shorter hospital stays for patients hospitalized in rooms overlooking nature, unlike patients in other types of rooms (Bates Smart, 2019).

Picture 2: Patient room, Royal Children's Hospital. Source: McGrath, Shannon (Photography). https://www.indesignlive.com/the-peeps/bates-smarts-mark-healey-healthcare-design

Another example is Khoo Teck Puat hospital, located in Yishun, Singapore (Picture 3), opened in June 2010. The architectural project was in charge of CPG CONSULTANTS PTE LDT, and the landscaping was conceived by PERIDIAN ASIA PTE LTD, which holds a LEAF certification (Linking environment and Farming) and has already won several awards. It was created under the concept of hospital in a garden, focusing on sustainability through three key principles: (I) to elaborate gardens in a practical and self-sufficient way; (II) to create natural gardens with people in mind; and (3) to implement the landscape and ecological characteristics efficiently in the use of resources and energy (National Parks Board Greenroofs.com, 2020). In this way, by being able to maximize the creation of therapeutic green spaces and to offer high-quality environments, architecture can link indoors and outdoors, providing the view of the gardens from different angles.

Picture 3: Benches in the open space of Khoo Teck Puat Hospital. Source: https://www.ura.gov.sg/ms/OurFavePlace/events/bench/locations/khoo-teck-puat-hospital

Evidence-based design

The notion of evidence-based design (EDB) is essential for the development of spaces intended for health. It is proposed that to create spaces for people with special needs, which require a design for specific results, the project should be based on solid research and updated. According to the Center for Health Research, EDB defines itself as "...the process of basing decisions concerning the built environment on credible research to achieve the best possible outcomes" (3) (The Center for Health Design, 2018).

During the last 30 years, a number of researchers have elaborated several works linked to the area of sanitary project, open spaces in the surroundings of health and restorative landscapes. Roger Ulrich is one of the most cited international researchers in this area. He began his career in 1979 as an assistant professor, researching environmental aesthetics, where he discovered that most landscapes of nature produced positive emotional states and helped relieve stress. His studies are still being implemented by design professionals and managers of medical care centers.

In 1984, Ulrich (Center for Health Systems and Design, Texas A&M University) presented a significant study on the positive influence that landscapes have on health outcomes. Patients recovering from gallbladder surgery were analyzed. Some stayed in rooms overlooking the trees and had fewer complications, used smaller doses of painkillers, and returned to their homes more quickly, compared to patients who had the view of a wall.

Ulrich and his colleagues carried out some researches and proved the "Theory of stress reduction", which demonstrates that five to seven minutes in contact with nature or looking at a natural landscape can:

- Reduce physiological indicators of stress.

- Improve the mood.

- Help recovery.

From 1991 to 1999, Ulrich presents "A theory of supportive gardens" (Ulrich 1991, 1999), which began in a previous conceptual work aimed primarily at architectural and interior design aspects of health facilities, but which has been modified and updated to focus directly on gardens. It shows that the ability of gardens to have healing influences comes largely from their effectiveness in facilitating health recovery and facing stress.

(3) It is the process of basing decisions on the environment built on a reliable search to achieve the best results. The use of quantitative and qualitative research to design surroundings that facilitate health and improve results.

Ulrich proposes that gardens are important stress-attenuating resources for patients and professionals, in addition to bringing improvements in clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction and the cost of care, as long as they fulfill the following guidelines:

- Create opportunities for physical movement and exercises.

- Offer opportunities for decision making, having privacy, and experiencing the sense of control.

- Provide settings that encourage people to get together and experience social support.

- Provide access to nature and other positive distractions.

The theory also argues there is a necessary condition for the four features above mentioned to be effective: the garden should convey a sense of security. If the design or characteristics of a garden produce feelings of insecurity or even risk, it is likely the environment will have a stressful influence, rather than a restorative one. And many patients, visitors and staff will prevent people undergoing medical treatment from feeling psychologically vulnerable.

At the same time, in 1995, a research concerning gardens in hospitals was published: "Gardens in healthcare facilities: uses, therapeutic benefits and design recommendations" (Cooper & Barnes, 1995), from University of California, Berkeley (4), which studied four gardens in hospitals located in the San Francisco Bay Area, California.

Interviews, behavioral mapping, and visual analysis were elaborated. It was discovered that stress reduction, including mood recovery, was the most important category of benefits enjoyed by almost all garden users: patients, family members, and employees. According to these studies, the traditional elements of gardens, such as lawns, trees, flowers, and water elements are appreciated: 90% of garden users experienced a positive change of mood after spending some time outdoors.

(4) It is the first systematic evaluation after the occupation of the outer space of hospitals.

In 2008, the " Theory of the Restoration of Concentration" was proposed, which proves that exposure to nature restores concentration capacity after concentrated efforts that create mental fatigue. This theory was developed by Rachel and Stephen Kaplan (Pati and Barach, 2008) colleagues and alumni of University of Michigan. A study was conducted with 32 patients in two Atlanta hospitals after a 12-hour shift. Sixty per cent of those with access to nature improved their vigilance or remained the same, and those without access to nature or without a view of natural landscape decreased 67% in surveillance. This research concludes that improving restorative quality of recess areas can lead to reduced stress and better patient care.

In 2015, a scientific study was initiated in Japan to investigate the decrease in depressive symptoms and increased memory performance in elderly adults, it was called "Effects of exercise and intervention on brain and mental health in older adults with mild memory problems and depressive symptoms" (Makizako et al., 2015).

Initially, the trial was conducted for 20 weeks, with 90 adults over 65 years old living with memory problems and depressive symptoms. Participants were randomly assigned to perform three experiments: exercise, horticultural activity, and educational control group. They conducted a combined program of exercises and horticultural activities during 20 weekly sessions of 90 minutes each. Participants in the exercise group practiced aerobic exercises, muscle strength training, postural balance training and double task training. The horticultural activity program included activities related to culture, such as cultivation in the field and harvesting.

Preliminary results observed antidepressant effects among old people with mild depressive symptoms and clinically significant symptoms of depression, suggesting the prescription of structured exercises with mixed elements of resistance and strength training adapted to individual capacity. The results of horticultural activity showed reductions in agitation levels, it was considered to be necessary to carry out well-designed intervention studies to examine the effects of horticultural activity on brain and mental health (e.g., depressive symptoms, cognitive function and brain volume) in non-demented adults at increased risk of dementia.

What is a therapeutic garden?

It is a delimited garden space intended for a given population with a specific purpose. The design of the physical aspects and the activities to be developed in the garden are based on medical research. It is recommended to be designed by a specialized multidisciplinary team, as it is a meeting point between medicine and design. The purpose of the therapeutic garden is to offer its users (patients, visitors, residents, employees) a place that contributes to improve their physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs, as well as helping them keep in touch with reality and providing well-being.

For Naomi Sachs (5), the definition of "healing garden", "restorative landscape" or "landscape for health" is that of any wild or projected space, large or small, that favors health human well-being (Sachs N. , 2016). Sachs proposes that private residential gardens can also be healing gardens, although there is a distinction to be made between curative gardens for all and curative gardens for people who have compromised health.

Picture 4: Joel Schapner Memorial Garden, Cardinal Cook Hospital, New York City. Source: Bruce Bruck (Photo)

https://dirtworks.us/portfolio/joel-schnaper-memorial-garden/

The former are designed to help healthy people stay healthy. It works like some kind of preventive medicine. However, in health facilities, the design process should be carried out with the greatest attention, taking into account users, and giving preference to evidence-based projects (Sachs N., 2018).

(5)Naomi A. Sachs, PhD, MLA, EDAC, Assistant Professor, Department of Plant Science and Landscape Architecture at the University of Maryland and Founding Director of the Therapeutic Landscapes Network (www.healinglandscapes.org)

In order to provide therapeutic benefits, the garden needs to meet a number of features such as: (I) a wide variety of plants that are distinguished by the changes of season; (II) views of the sky; (III) small lakes of water and trees that can attract wildlife; (IV) scheduled activities, such as horticultural or rehabilitation therapies, ensuring universal accessibility; (V) well-defined perimeters, so users can focus their attention on the components of the garden, that means the functional organization should be clear and simple with an orderly structure of the circulation to facilitate orientation and mobility user.

Benefits of being in contact with nature

There are many benefits of being in contact with nature, including physical, psychological, social and personal aspects. Spending only 90 minutes a day in a wooded area reduces depression, and spending one day in nature in a recurring way improves the immune system.

Experts have recorded great benefits in the use of gardens, parks and green spaces, both inside and outside health environments, such as: stress reduction, sleep improvement, anxiety and depression reduction, associated with increased happiness, reduced aggressiveness, reduced behavioral disorder symptoms, decreased blood pressure, improved recovery of surgeries, improvement of overall health, increased life expectancy in older adults, if they have access to parks and nature, improvement of quality of life in chronic or terminally ill patients, besides helping patients to evoke their own healing capabilities (Frumkin, 2017).

Design strategies for a therapeutic garden

Ulrich proposes four design guidelines for conducting a therapeutic garden: exercise, sense of control, social support, access to nature and other positive distractions in "A Theory of Supportive Garden Design" (Ulrich, 2001). In addition to these basic guidelines, the author's observation on hospital gardens in the United States, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom highlights the need to consider that, in order to be used and reach its full potential, it must possess the following qualities: visibility, accessibility, familiarity, tranquility, comfort, and art without ambiguities.

Clare Cooper Marcus, in her article "Healing Gardens in Hospitals" (Cooper, 2007), describes some essential design elements and environmental qualities that a therapeutic garden should have, and describes the precedents used by designers of contemporary healing gardens, including those for medical diagnosis, where a number of pathology design recommendations have been proposed. On the other hand, the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) and the American Horticultural Therapy Association contributed to the development and understanding of the elements for the design of therapeutic landscapes, approving the document "Therapeutic Garden Characteristics" (Hanzen, n.d.), which serves as a reference for medical professionals and landscape scholars in relation to well-being. The combination of these fundamental elements represents current practices for therapeutic gardens.

Picture 5: Gardens at Centro Sociosanitario Geriatricatrico Santa Rita/Manuel Ocaña. Source: De Guzmán, Miguel (2009). https://www.plataformaarquitectura.cl/cl/626312/centro-sociosanitario-geriatrico-santa-rita-manuel-ocana

Conclusions and Recommendations

The following table, taken from our bibliographic review, summarizes the design strategies for creating a therapeutic garden.

| Scheduled activities | Promote activities that bring special populations, families of patients and residents of the community near the garden. Activities that may occur outdoors can be active or passive, for an example, contemplation, rest, meditation, praying, waiting room, rehabilitation exercises, food, reading, walking, hiking, gardening, horticultural therapy, ecotherapies. |

| Universal accessibility |

Adapt the garden environment to provide accessibility, facilitate gardening tasks, improve visitors' experience by allowing them to be in contact with plants. Paths must be wide enough, paving joints should not be high and must be narrow enough not to hold a cane.

|

| Well-defined perimeters | The edges of the spaces and special areas of activities within the garden should be well demarcated so that the user can focus his attention on the components of each zone within the garden. Gardens that have areas with clearly defined functions and include direction and location indicators allow users to behave and use the space more independently. |

| Adhering of plants and interactions between people and plants | Provide varied plant material with distinct changes in leaves, colors, textures and shapes, so people can experience planting, growing and flowering seasons. Provide routes with open and closed views, to generate experiences of different spaces with surprise elements. |

| Beneficial and supportive | Create outdoor play areas that allow people to walk, relax or rest in shaded spaces, whether with protective structures such as pergolas or with plants, offer personal comfort and shelter to garden users, provide support settings such as handrails, frequent presence of seats with armrests and backrests. |

| Creating recognizable places | Therapeutic gardens are simple, unified and easy-to-understand places. The functional organization should be clear and simple, favoring relationships, an orderly structure of circulation, continuity and clarity of paving will facilitate mobility and user orientation. |

| Water devices | he placement of water devices attracts wildlife and are increasingly used in health facilities as they can serve as reference points, guidance elements, as well as function as positive distractions that reduce stress. |

| Medical diagnoses | A therapeutic garden can bring benefits to many categories of users, so it is advisable to know the medical needs of users and their caregivers so that it is possible to create spaces that can function as a means of treatment and meet the needs of users as appropriate. |

Table 1. Recommendations for the design of therapeutic gardens.

Some special recommendations for the design of outdoor spaces in nursing homes, rehabilitation gardens for people who have suffered cardiovascular accidents and gardens for patients with Alzheimer's disease.

| Residences for the elderly |

|

| Rehabilitation gardens for people who have suffered cardiovascular accidents |

|

| Gardens for patients with Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia |

|

Table 2: Recommendations for the design of gardens for the rehabilitation of special pathologies. Source: Cooper, (2007), Healing Gardens in Hospitals.

References

BATES Smart. (2019). The Royal Children's Hospital - Architecture. Available at: https://www.batessmart.com/bates-smart/projects/sectors/health/the-new-royal-childrens- hospital-architecture/

COOPER, M. C., Barnes, M. (1995). Gardens in healthcare facilities: uses, therapeutic benefits, and design recommendations. The center for health design. Universidade da California, Berkeley. Available at: https://www.healthdesign.org/sites/default/files/Gardens%20in%20HC%20Facility%20Visits. pdf

COOPER, M.C. (2007, janeiro). Healing Gardens in Hospitals. Design and Health, IDRP Interdisciplinary Design and Research e-Journal.

Volume I, p.4-6.

FROMM, E. (1973). Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, p 261. Retrieved in 2018, Dispose of it in: http://www.ignaciodarnaude.com/textos_diversos/Fromm,Anatomia%20de%20la%20destruc tividad%20humana.pdf

FRUMKIN, H., (2017) Seattle Parks and Recreation: Parks, Greenspace and Human Health. (Video) Available at: http://www.seattlechannel.org/misc-video?videoid=x71138

GOLLINGS, Jhon. (2012). Royal Children's Hospital landscape. Retrieved in May 18, 2017, from https://architectureau.com/articles/new-royal-childrens-hospital/#

HANZEN, T., (s.f). Therapeutic Garden Characteristics. A quarterly publication of the American horticultural association. Volume 41, Number 2, p3. Retrieved in 2017 from https://www.ahta.org/assets/docs/therapeuticgardencharacteristics_ahtareprintpermission.pdf

MAKIZAKO, H., Tsutsumimoto, K., Doi, T., Hotta, R., Nakakubo, S., Liu-Ambrose, T. & Shimada, H., (2015). Effects of exercise and horticultural intervention on the brain and mental health in older adults with depressive symptoms and memory problems: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1032-3

National Parks Board Greenroofs.com. (2020). Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH)

PATI, D, Harvey TE Jr, Barach P., (2008). Relationships between exterior views and nurse stress: an exploratory examination. HERD. 2008 Winter; 1(2) p27-38.

SACHS, N. , (2016). What is a healing garden?. Retrieved in May 2017, from: https://healinglandscapes.org/what-is-a-healing-garden/

SACHS, N., (2018). Healing Landscapes. Retrieved in January 2018 from: https://aiacalifornia.org/healing-landscapes/

The Center for Health Design organization. (2018). The center of health design. Available at: https://www.healthdesign.org/

ULRICH, R. (2001). Effects of Healthcare Environmental Design on Medical Outcomes. Design and Health: Proceedings of the Second. Recuperado de:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273354344_Effects_of_Healthcare_Environmental_Design_on_Medical_Outcomes

ULRICH, R.S., Zimring, C., Zhu, X., DuBose, J., Seo, H., Choi, Y., Quan, X. & Joseph, A., (2008) A Review of the research literature on Evidence-Based Healthcare Design. HERD, Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1 (3), 61-127. Retrieved in July 2017, from www.herdjournal.com issn: 1937-5867: www.herdjournal.com issn: 1937-5867

WILSON, E.O. (1984). Biophilia, the human bond with other species. Harvard University Press, Cambrige (Massachusetts).

Authors

Valentina Moya, Architect, Landscape Architecture Specialist. Tabora+Tabora Office/landscape architects.

Email: arq.valentinam@gmail.com.

Sonia Cedres de Bello, Professor-Researcher at the Institute of Experimental Development of Construction. Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism of the Central University of Venezuela.

Email: bello.sonia@gmail.com

Send by e-mail: