Publications IPH Magazine Revista IPH Nº17 A study on the development of the concept growth and change on hospital architecture in Japan

- IPH Magazine #17

- COVID-19 pandemic and the trends in healthcare design: insights from the "Decalogue for Resilient Hospitals"

- Healthcare closer to people: A qualitative study of a Swedish reform on healthcare delivery

- Spatial flexibility and extensibility in hospitals designed by João Filgueiras Lima

- Design Insights from a Research Initiative on Ambulatory Surgery Operating Rooms in the U.S.

- A study on the development of the concept growth and change on hospital architecture in Japan

- A study on hospital infection control through architecture in 1980: Chapecó Regional Hospital case study

- Natural ventilation for hospitalization environments: historical aspects

- Hospital architecture and its propositions for beginners and experts

A study on the development of the concept growth and change on hospital architecture in Japan

Kazuhiko Okamoto - Toyo University, Japan

This study aims to find how the concept Growth and Change on hospital architecture proposed by U.K. architect John Weeks has been introduced and developed in Japan. Literature review and interviews were carried out and the findings are as follows; 1) John Weeks was introduced to Japan by Professor Makoto Ito in 1965 followed by Weeks' concept Growth and Change by Professor Tadashi Yanagisawa in 1969 while similar concept has already been found by Rintaro Mori in 1899 and theorized by Masao Takamatsu in 1923; 2) After 1969, Weeks' concept has spread and was accepted throughout Japan through textbook and drawings of its application, Chiba Cancer Center, though some questions have been raised; 3) The concept has been found unsuccessful in the case of Northwick Park Hospital he designed in 1970.

Keywords: John Weeks, Richard Llewelyn Davies, Northwick Park Hospital, Evidence-based Design, POE, Hospital Planning History

1 Background and purpose of the study

It is a common understanding among hospital designers that hospital buildings are repeatedly expanded and reconstructed as medical care and equipment progresses, and when they reach a dead end, they are forced to be rebuilt. For this reason, hospital designs are often required to anticipate future expansions and rebuilds at the beginning of design. The concept of Growth and Change by John Weeks (1921-2005), a U.K. hospital architect, is often cited in such cases. Many of them are illustrated with the layout of Northwick Park Hospital, which he designed. It shows a long hospital street with space for expansion at the end of the buildings along the street and vacant lot for new construction at the end of the street. It is often said that this idea was born when he was looking at an old map of Ashmore Village in the U.K. and noticed that the buildings had changed but the road had not changed in 800 years. This study distinguishes between Growth and Change as proposed by Weeks and the general concept of growth and change which includes Growth and Change, which has become a very common concept in Japan. It also looks at when and by whom Growth and Change was imported and how it spread in Japan.

2 Past research

From the late 1960s to the 1980s, Shinya conducted a number of studies on the evolution of hospital layout and floor plan, which he summarized in his doctoral dissertation231) as a compilation. Similarly, Yoon245) also traced the layout and floor plan from the viewpoint of "building and medical standards," but none of them touched on growth and change or Growth and Change. Ueno et al.242) also summarized the planning history of hospitals in the post-war period, but only a few of them mentioned growth and change.

3 Research methodology

A literature review and interviews were conducted. In recent years, growth and change has become a common concept in hospital architecture as a precondition for proposals and design, therefore, the literature collected was limited to Yasumi Yoshitake's last book, Architectural Design Planning Pickup I, II (2004) 243,244), who is considered to be closely related to Weeks (although Ref. 245 is excluded). In addition to collecting literature on hospital design methods (excluding mere introductions to works) by going back through the reference list, including the previous studies mentioned above, we extensively surveyed medical journals and literature on hospital management. The literature was arranged in chronological order to determine whether the concept of growth and change existed in Japan before Weeks, who introduced the concept of Growth and Change to Japan, and how it spread.

What was not clear in the literature review was supplemented by interviews with Tadashi Yanagisawa (Professor Emeritus, Nagoya University) and Yasushi Nagasawa (Professor Emeritus, the University of Tokyo), who both had actually met Weeks and quoted Growth and Change in their works194, 196, 200, 227, 230, 239).

4 Findings

245 pieces of literature were collected and listed in the reference list at the end of this volume. Below, we describe when growth and change and Growth and Change emerge and how they spread across time periods.

4.1 Pre-war to mid-war period (before 1945)

The oldest document1) collected in this collection is an abridged translation of the Naval and War Department's Treatise on Hygiene by the First Head of the Dutch Naval Medical School, Murtin Melman (1866), but it already describes the space for expansion. Hospitals here refer to military hospitals and are classified into three categories: "temporary hospital," "main hospital" (which should be located near the main camp) and "true main hospital" (which should be located in the rear). As the number of patients in the war zone was able to increase rapidly and patients were transferred between hospitals of different types, so that the size of a hospital can not be determined by the number of men in the army.

There should be space for future patients in "true main hospital" site. While this is a translation, it is the first document that describes growth and change.

The first article3) in the inaugural issue of the Journal of Architectural Institute of Japan is a design method for clinic. "Clinic is what the architect have to pay the utmost attention when designing because that is the most difficult building in terms of design" is the beginning of the article, in which he explained that hospital building emerged in the 18th century and the building layout of Hôpital Lariboisière in Paris was the first perfect practice in this short building type history. In addition, he pointed out the importance of the view and clean air, which is in line with the current Evidence-based design, through the layout and sanitation of clinic buildings in Europe, saying: "If such a place has an open view and fresh air, patients will feel refreshed by themselves and their illnesses will be cured quicker." The dimensions of the 1,500-2,000 cubic feet of air volume per bed required to prevent infection, as well as the dimensions of eight feet between bed center lines are roughly in line with the figures in Florence Nightingale's "Notes on Hospitals" (1863).

Mori5) was the first to mention the "corridor" and "pavilion" style of building arrangement, as well as hospital trains. Mori compiled many hospital design methods based on his four years of dispatch to Europe from 1884, and he explained in the second edition13) that the Oresunder Hospital in Copenhagen had prepared a 320-square-meter/bed site because "they will require space on the premises for additional buildings to be built on other days." It was Mori who first became aware of the concept of growth and change, through what he had learned from the Danish case study.

A report by the Architectural Institute in U.K., introduced by Ishii16), states that "Even though many hospitals nowadays bear the stigma of ill-health, the cause of this stigma is not due to negligence in the construction, enlargement, or remodeling, but mainly due to defects in the detailing of the building." This may be because, already in this period, there were some hospitals having failure to cope with growth and change and the buildings were not able to meet the sanitary needs. In addition, there is an episode17) in which someone named a hospital "a health factory," which shows the influx of a new concept of hospital in Japan.

It was Takamatsu31) who was most influential in hospital architecture during this period, and even referred to the theory of growth and change. He noted that, in the U.S., the plan of a hospital ward was designed to be flexible so that large rooms could be made smaller, and if expansion was expected to take place in the future, it needs to think about expansion in proportion to the size of the ward. In the case of large hospital, clinical department should anticipate future expansion. Therefore it is also important to think about the future development regarding hospital site. Thus, the theory of growth and change, first introduced to Japan, was learned from American examples. Takamatsu further divides the ends of the pavilion type into "open end" and "closed end," but he does not discuss the future expansion of the open end. As he said: "Hospital architecture can be thought of as a large, so-called instrument," he seemed to recognize that hospital architecture was a kind of medical equipment. He also stated32) that hospital facilities should be transposed to the grand architecture that organize the reconstructed capital after the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. That is to say, he compared the plan of hospital architecture to the urban planning for the first time. He wrote: "The orderly proportion and arrangement of each room and corridor on floor plan was achieved by land readjustment and reconfiguring roads and The unified arrangement of each part and the clinical and social classification and zone in patient wards are created by establishing and implementing their own regional characteristics of residential, commercial, industrial, and mixed communities." Unlike Ashmore Village, he supposed a good hospital can be created by scrap-and-build and zoning, which remind us a popular method in disaster-prone country.

On the other hand, Nagane35) measured the dimensions of hospitals in Kansai region and Tokyo and compared hospitals in Germany and the U.S. to describe the design of the entrance area. He counted the number of outpatients going in and out of the Keio Hospital in Tokyo, which he had planned, "as 40 people going out (for 4 minutes from 10:00 a.m.), 21 people coming in," and judged that the number was too large for the dimensions of the entrance, then proposed an example of improvement. This is the first example of improvement in which not only numerical evidence was collected, but also a POE (Post Occupancy Evaluation) was carried out and reflected in the design.

The first systematic textbook in Japan by Yoshida37) also explained the design method using examples from abroad, including the U.S., the U.K., Germany, Austria, and Denmark, which stated: "Vacant spaces between wards should be as close as possible each other unless blocking the sunlight to the rear wards in order to save land and traffic labor, and to remove a risk that vacant spaces between wards will be used for future expansion," suggesting that an unplanned expansion had already taken place. It also states: "A building itself must be considered a means of medical treatment. The treatment of patients will be further promoted if the environment, facilities, lighting, ventilation, temperature, and humidity are as perfect as possible in a hospital room. Herein lies the importance of hospital architecture." Although the scope of the article is rather narrow, the author indicated the perspective of hospital architecture as a treatment device.

Other important aspects of hospital design are mostly brought to the pre-war period, such as Osawa45) and MT55) (note: anonymously, but Takamatsu Masao) who organized hospital equipment, Takamatsu48) who described wayfinding and Kondo60) who emphasized patient privacy while simulating the number of steps a nurse would take.

Osawa63) said:"Today is the Age of Health. Hospitals are both instructors and patrons of health" suggesting that in a broader sense architecture affects health. In the third edition of the same book64), in addition to Nagane's statement35), "There are many theories about the number of latrines, and some say one latrine for every 30 patients, but in my experience, when there are more than 500 to 600 outpatients, there are a few cases where one latrine is provided for every 25 patients even the urine examiners use this facility." He made such a scale planning using numerical evidence based on precedents and observations.

Ref. 66 is the hospital section out of a 26-volume systematic textbook, in which Takamatsu shows many examples of photographs and drawings from Europe, the U.S. and Japan, while also addressing the nightingale as an architect.

According to Takeda68), "There always comes a time when a hospital needs to be expanded and enlarged, and it is unavoidable to build on a narrow site without much space so that finally hospital will have to move or be left as an obsolete one. Therefore, hospital buildings should be built on half or one-third of the site as a high-rise building from the beginning."

4.2 Post-war to reconstruction period (1945-1959)

Ref. 87 is a serialized translation of "Design and Construction of General Hospital" by Marshall Shaffer, U.S. Public Health Service Senior Engineer, in Architectural Record from August 1945 to August 1946. It says: "The most typical general hospital of the 40-bed type is fundamentally expanded to 50-60 beds and It is necessary to consider that in the future it may be necessary to add facilities that may not be employed at present." Specific design techniques such as Minimal configuration and services, Facilities such as laundry or anatomy rooms can be omitted according to local conditions, Surgery, delivery, emergency, etc. should be separated, and Administrative wing can be expanded are shown

with drawings.

Ref. 102 is also a translation of the same "Design and Construction of General Hospital" as Reference 87,118-121, but out of the four parts of the diagrammatic plan (model plan), design and structure, elements of a general hospital (detail drawings) and equipment table, only elements of a general hospital is picked up.

Ref. 107 deserves special mention as a step-by-step design method that anticipates growth and change from the beginning. The reason for this is that although reinforced concrete construction was prescribed for hospitals due to post-war requirements for fireproofing and seismic resistance, this was still an economically difficult time. "It is easy to build a wooden extension, but with reinforced concrete, it turns difficult to construct a limited part of the department, within limited budget, which prepares the building, piping and wiring connections to expand in the next budget period." Therefore it must be an architecture that integrates the limited functions of the first phase with future functions, traffic lines, and plumbing that will be connected to the second and later phases, in artistic shape.

Around this time, the plan of 186-bed wooden general hospital model plan by the Central Council for Medical Institution Development (hereinafter referred to as Yoshitake Model Plan), which Yoshitake led, appeared in rapid succession96,103,104,106). Yoshitake Model Plan included 53 design tips along with the first and second floor plans, and stated that the site should be large enough to accommodate the need for sufficient vacant space around the building to maintain the hospital's environment, and since all hospitals will need to expand in more than ten years, the site should be large enough to accommodate these requirements. Yoshida103) even commented on the reduction: "I think it is possible to stack them appropriately, or to expand them to accommodate more beds, or to reduce them to small hospitals." Since Yoshitake does not mention expansion in the text, the site size requirement in Yoshitake Model Plan for expansion might have been proposed by Yoshida. However, there is no word to the reduction in the process of preparing Yoshitake Model Plan in Ref. 232 or in the "Text of Professor Yukio Yoshida" in Ref. 244.

Here Yoshitake112) suddenly questions the preparedness for expansion. "The problem with the high-rise layout of ward blocks is the difficulty to meet the future expansions and annual budgets from the government. Expansion, which was extremely important under the traditional concept, may become less of a problem when the hospital is considered a component of a national organizational network. This may mean that if the U.S. hospital function sharing system is introduced, the functions of each hospital will be fixed and will not need to be expanded or reconstructed." This is the only paper in this study that suggests that expansion will not be a problem.

Richard Llewelyn Davies, co-researcher and designer of the Weeks, appears in Yoshitake's London Architecture Research Conference Report113). Hospitals were presented in three papers, and "the first two hospitals are notable papers that are based on research into the actual use of buildings and are aimed at new developments in functional design planning. This type of research was rare in Europe and the U.S.. It is a pity that there was no reflection on what they designed," he said with POE-prone viewpoint. The first paper is a report on the ward survey by Davies and concludes with the following statement: "Hospital services change and create new solutions as medical and social developments occur. Hospital research is not about seeking a fantastical solution to all problems permanently, but rather the accumulation of knowledge and experience of hospital problems, which is never completed in that sense." The third paper is by Marshall Shaffer, who appeared in references 87 and 102, and lays out the special points on hospital design developed by the Hill-Burton Act in 1946. "Clinical part of the hospital is most susceptible to change. Consider future developments."

Osawa's Ref. 115 was an addition to Ref. 64 and added the phrase, It is even said that the site should be enough to accept hospital expansion by 100%. This specific figure "100%" was often mentioned until much later118-121,123,140,145,193), but the basis for this concrete percentage probably originates from Ref. 87, as explained below.

Ref. 118-121 are translation of "Design and Construction of the General Hospital," same as Ref. 87 and 102. It consists of four parts: a diagrammatic plan (model plan), design and structure, elements of a general hospital (detail drawings), and equipment table. "It is necessary to be able to expand at least 100% of the total floor area to be built therein in the future, and it is also considered to expand the structure. In any project, it is important that the future expansion plan is thoroughly considered." Ogawa notes that after the completion of the first part of Ref. 118, at the author's request, the work was resumed for the time being, and then ended, because the expanded version, including the model plan, was released in the U.S.. The next version, translated by Ogawa in 1955119), was based on the translation of the supplementary edition, as well as on Ogawa's translation of the criteria and model plan for the Japanese ward and outpatient departments and on a translation of the "Mental Ward Attached to the General Hospital" by G. Guttersen of the U.S., but the content of the translation remained largely unchanged.

On the other hand, Yoshitake's translation in 1956120) gives a detailed account of the translation process in the preface. The original was published in Architectural Record in 1946, but in 1950, Yoshitake group first came across a French translation in L'Architecture d'aujourd'hui, April 1948 issue. Although Japanese translation from the French was in progress, he obtained the original (probably an enlarged version) at the end of 1953 and worked on it at once, and it was expected to be ready for Publishing in the spring of 1954. However, the translation was delayed until 1956 due to Ito's convalescence and Watanabe's death. In addition to this delay, the fact that article includes a letter from Marshall Shaffer stating his acceptance of the translation and that Yoshitake and the U.S. Public Health Service had agreed on a unified translation for the book suggests Yoshitake and Ogawa were rivals.

Takano123) wrote about the site: "I would like to have a site that can accommodate a building about twice the size of the original plan for future expansion. It would be sufficient for a block-type building to be 100m x 100m for 50 beds, 150m x 150m for 100 beds, 200m x 150m for 200 beds, and 200m x 200m for 300 beds."

Yoshitake126) describes each department based on American-style hospital management and evaluates three hospitals in the U.S. The central treatment department was positioned as a central facility where "advanced facilities are added or changed in response to the progress of medicine." Regarding the idea of dividing the central treatment department and wards into separate buildings and connecting all floors with a corridor, the report negatively says: "It is convenient to have a central treatment facility on the same floor that corresponds to the wards and the central treatment facility, and there is less congestion of elevators, but on the other hand, the connection with the wards is not always on a one-to-one basis and there is a lack of flexibility for future development." The reason for the difference in assessment with the current approach of making patient wards in independent building which grows and changes less is probably because of the impossibility of combining wards and central medical departments in the same department on the same floor.

Ref. 137 and 138 are encyclopedias of architecture and revised in 1980216). 1956 edition recommended to adopt the new hospital management systems and standard designs because of "full of examples of how each successive expansion has made the system more disorderly and recommended to consider the rapid advances in medicine, medical practice and the development of the community at the same time." It also states that the ceiling should not be set too high, which is a different approach from the current design. This is because "a hospital is divided into small rooms, and it is advisable to decide carefully not to raise the ceiling too high in view of the mood of the rooms and the economy. Note that the ceilings of operating theaters and X-ray rooms may be higher than others."

Ref. 153-155 does not describe growth and change in the paper by Yoshitake, Ito, Ura, Kurihara and others on the architectural side, but describes the prospects for future changes in volume study and functional allocation as new hospital management becomes widespread. In contrast, the medical side156) said "It is natural that a block system will be adopted. However, even then, we should have some foresight about future expansions and consider measures to deal with them. Block systems are far more difficult to expand than pavilion systems, and yet not a few of them do not take this into account at all."

4.3 Rapid economy growth period (1960-1979)

Ref. 164 is a design collection. In the section "Flexibility is required for all buildings and facilities," it states that "buildings and equipments must always be planned with enough flexibility to accommodate such movements" which mentions for the first time the relationship between growth and change and equipments. In addition, the collection of layout drawings places a "first-class plan of Architectural Institute of Japan competition design" at the beginning, emphasizing that the layout is ideal and prepared for future expansion as well.

In contrast, Ref. 165 is a design textbook. In the Foreword, Yoshitake says that he wanted to clarify the significance and content and to deal with the basic policy of the plan in depth and broadly because Ref. 164, which he also edited at the same time, focuses on design methodology. While he states "it is not necessary to raise the ceiling height too high except for the boiler room, kitchen, operating theater, and radiation therapy room," equipment replacement was taken into account saying "In particular, regional hospitals need to leave space for future expansion, not only to increase the number of beds, but also to improve the standard of medical service in the region as a whole by improving treatment departments." There is also Davies in the index, but Weeks, growth and change and Growth and Change have not yet appeared in the index.

Ref. 166 is a revised version of Ref. 165, with the underlined sections added and changed. "Consideration of future expansion is particularly necessary in hospitals. The potential for expansion varies from department to department and is especially great in the treatment department and patient ward. The decision on the floor height in the initial plan will affect the subsequent expansion plan, since hospitals with frequent cart movements will not have steps or ramps. Except for the boiler section, kitchen, operating theaters and radiation therapy rooms, the ceiling height does not need to be very high and can be the same" and the reference reads "It is not good to be too low as a whole, but it is more convenient for future additions to have a uniform height that is not too high. Also, extensions above the building should be avoided." There is no change in the index, so Davies is there, but Weeks, growth and change and Growth and Change are not yet available.

Ito182) states that "the architectural standards of some of our country's hospitals have already reached a considerable point," and Weeks appears for the first time in one of the issues "Hospitals with Hands" as "John Weeks has an insightful view as he cites hospitals, universities, laboratories, and airports as examples of buildings that are in a state of rapid change and calls them Indeterminate Architecture. Designing a hospital that will grow with time always requires a master plan that looks ahead to the future. It would be necessary to make an overall plan for the future as much as possible at this stage, and in any case, an attitude of constructing a part of it first. The above can be further translated architecturally as follows: Hospitals, depending on their scale, should be designed with as many wings as possible and their ends should be free endings. In other words, they should be divergent. It goes without saying that boilers and electrical equipment will need to be added as a result." While not mentioning the word Growth and Change, it details even aspects of the equipment, citing progressive patient care, linear accelerators, hyperbaric oxygen chambers, medical equipment and rehabilitation as causes of expansion and transformation.

Nikken Sekkei183) says "We have tried to respond to changes and additions. However, it is not possible for us architects alone to think about what treatment methods will be available in the future," calling for joint design with other professions. Around this time, suggestions for growth and change from practitioners began to be introduced, and the authors also discussed the need for hospital architects and consultants188,192,204,215).

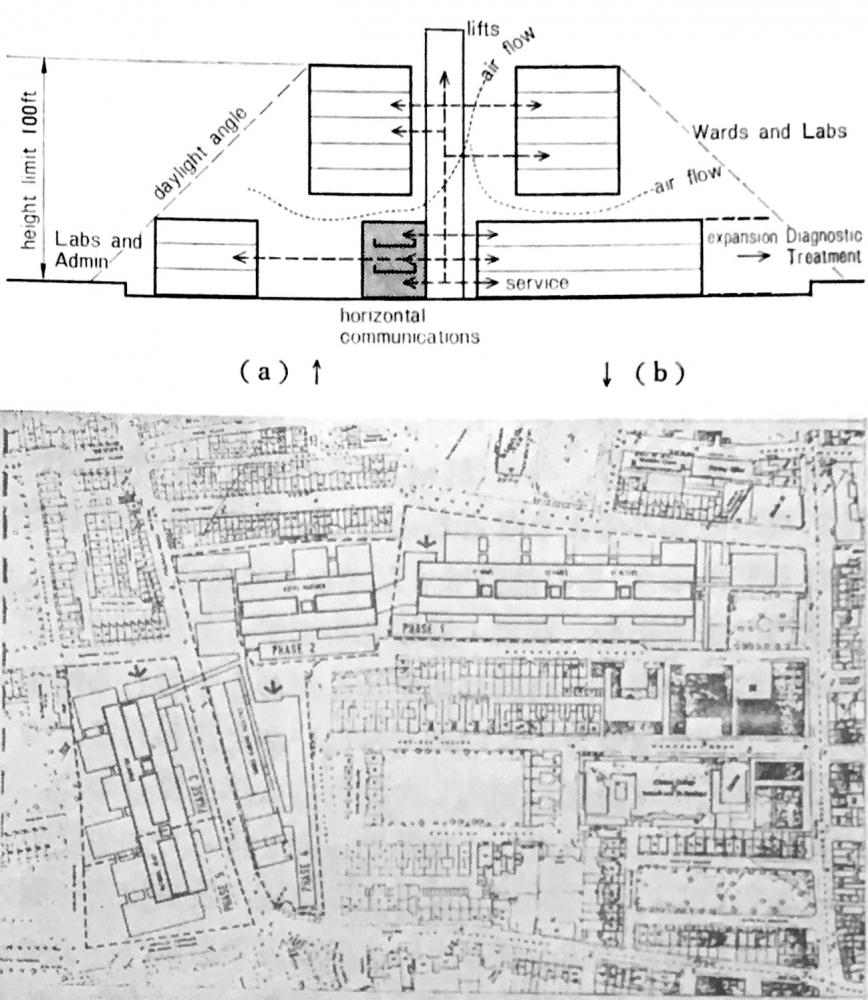

Here, Yanagisawa194) introduced Growth and Change for the first time, and a whole chapter was devoted to Growth and Change. This is also where growth and change appears in the book. Based on a survey of 10 hospitals in Aichi Prefecture, he discusses the causes of expansions and renovations, and introduces Northwick Park Hospital as an example of Indeterminate Architecture, with its layout and operating department expansion system.

Yanagisawa and Imai196) visited Weeks to show the design and construction site of Northwick Park Hospital, and also introduced the personality of Weeks and his office, explaining the theory and practice of Indeterminate Architecture with figures and photos. The latter half of the book concludes with an introduction to the plans of four overseas hospitals in consideration of Growth and Change and a proposal for the future of Growth and Change by comparing a case study of hospital expansion and renovation in Aichi Prefecture, which was introduced in Ref. 194. The general path, planning of structures and facilities that can be changed internally, identifying and separating the departments that will have growth and change are mentioned.

Furthermore, Yanagisawa200) reported on the construction site of McMaster University Hospital in Canada, which Weeks encouraged him to visit. The idea of combining a variable interior with basic structure of a large steel truss structure with Interstitial Space is not without problems, and he points out the difficulty of moving partition walls, the irrationality of dividing a small room into a large span, the difficulty of building an extension in the center of the building and many windowless rooms. He also poses the question of whether a rational system and a humanistic space are compatible and advocates a network from acute care to welfare.

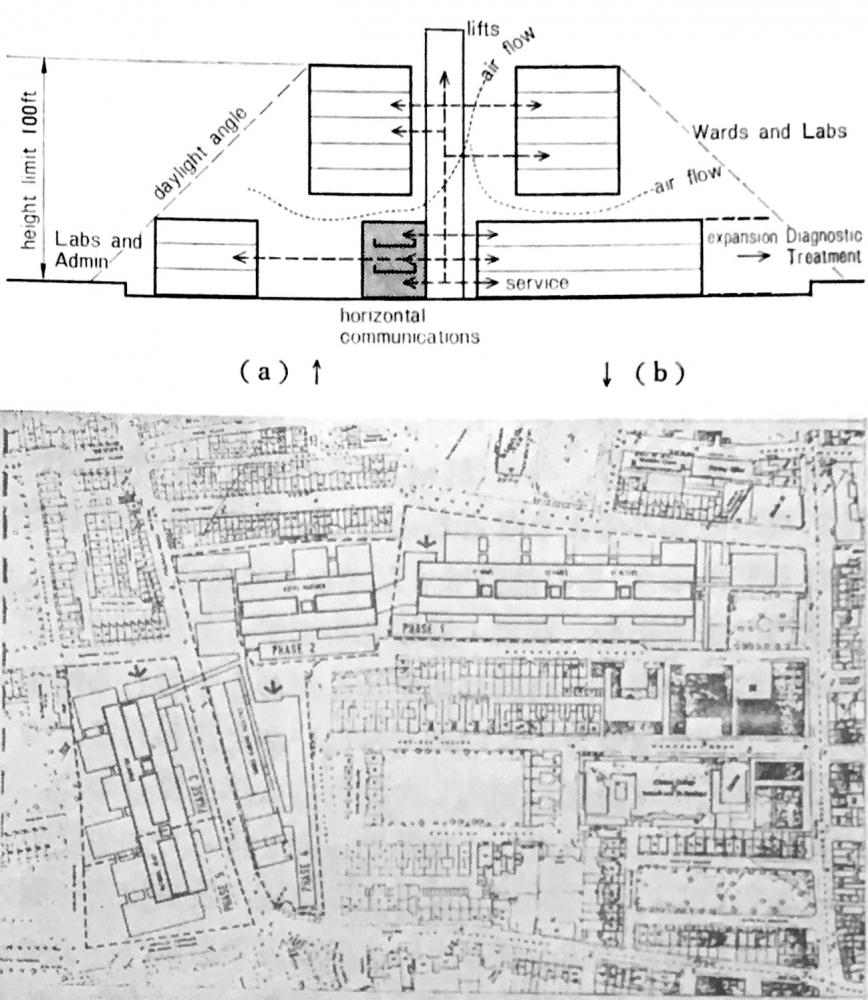

Ref. 210 is a special issue that discusses the changes in hospitals from various perspectives, including medicine and economics. In the architecture section, Yoshitake wrote an essay entitled "Hospital Architecture of the Future" based on Nightingale's writings. There is no specific explanation, but it is accompanied by a diagram entitled "Plans for the redevelopment of several hospitals in London" (Fig.1, Davies, Weeks and others: a proposal around 1960, captioned in Ref. 210). Although Davies and Weeks are not mentioned, "Hospital has changed from a pavilion type to an "organic block" type, which is still in use today. In recent years, as building regulations in cities have become increasingly stringent and neighbors have become opposed to the idea of a giant building, it has become difficult to maintain this form, and it seems to me that hospitals would be better off going in the direction of amorphous rather than standard forms. In other words, the hospital should conform to the requirements of the regulations and be fluid in form, while each department should be strictly functional and complete, and each department should be connected to the other by using the latest construction and equipment technology." He advocates Indeterminate Architecture from the perspective of building regulations instead of growth and change. In order to realize this, "Prefabrication is unavoidable in the construction method and it is necessary to pursue the structural system, equipment wiring and piping system in parallel. Even if the external appearance of the hospital is destroyed by this kind of amorphism, each of the internal departments should be completed satisfactorily by pursuing new functions."

Fig.1 Several hospital redevelopment plan in the city of London, a proposal to build sequentially along the streets (b) in one system with section (a)

In an independent book on the design method and the actual work by Ogawa211-213), he wrote: "The eight medical function groups can expand freely and will begin to grow around the central basic room as their contents change and enrich themselves with the development of medicine. The growth is not necessarily continuous but could be irregular, therefore the hospital architecture must be an instrument which can respond to them. It is also poetically stated that Extensions and alterations are considered to be an architectural molting phenomenon, and this molting, which comes after maturity, may conceivably have a deeper meaning than nurture or maturity. Therefore, those who are planning additions and alterations must always ask about the past growth history of the hospital, analyze the contents of the present maturity and draw the future image of the hospital through additions and alterations."

4.4 Bubble economy period and later (1980-2004)

Ref. 216 is a revised version of Ref. 138. It includes a section "Space for future expansion," where the site area is quantified as "at least large enough to keep the floor area ratio below 100% as a rough guide." In the section "Responding to growth and change," it was noted that "All buildings are forced to be rebuilt, expanded or renovated in step with the times. This is especially true in the case of hospitals, and how buildings should respond to the growth and changes in their functions is now a common challenge to all countries." It shows the connecting corridor plan, the Chinese character "king"-shaped plan (outpatient department, central diagnosis department, and wards are arranged in parallel from the south and connected by central corridors), and the consolidated plan followed by the multi-winged plan, which is a "block plan that aims to respond relatively freely to growth and change without losing the organicity and functionality that are the strong points of the consolidated plan" with the building layout of Chiba Cancer Center. It also includes a new section "Responding to the growth and change in clinics," which specifically states "Nearly half of the clinics that have been in business for less than 10 years, more than three-fourths of those more than 10 years, and about 80% of those more than 20 years have expanded or renovated," and "The floor of treatment department in clinics with beds has increased significantly, from several times to nearly 10 times the size."

Ref. 218 divides nursing into Intensive Care and Total Care, and because it is the former that is changing, "In planning, it is advisable to place more weight on the latter, and to assess the trends and factors in the former before addressing them" and urges planning from a nursing perspective, which has never been done before. It also describes design techniques such as open-ended corridor, partitions by dry construction and equipment space, citing a departmental growth rate and acceleration study by Davies and Weeks.

Ref. 222 is a translation of "Hospitals and Health Care Facilities," McGraw-Hill, 1978, by the American architect Louis Gordon Redstone. The words growth and change are not used, but referring to the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid in the U.S., he wrote: "Because of the rapid developments and changes, not only in terms of health insurance, but also in terms of the demands of the medical profession and the community, the planning of new hospitals should be designed to allow for maximum flexibility and there is an increased focus on considering future incremental development." However, as "few hospitals are able to adequately respond to future changes in health care, the facilities currently under planning must be designed to accommodate the maximum amount of change or they will be obsolete upon completion. To this end, along with a large site and permanent corridor space, the main corridors, stairways and elevators should not be altered unnecessarily, so as to determine the pattern of the hospital's expansions and renovations and to ensure that traffic routes are easily understood." It is also specific to show "flexible and changeable transportation systems, long-span column in anticipation of internal changes and lateral expansion, easy-to-demolish buildings and reduction of built-in equipment." The American way is that "profitability with respect to safety is as important as the relationship between quality and cost of architecture. Hospitals are no longer immutable and need to change constantly; they should be rebuilt on a 20-year or so cycle, with the expectation that there will be fundamental changes in 10 years or so," a bold scrap-and-build proposal. The case study describes in detail the concept of Northwick Park Hospital and Weeks, but it quotes only Indeterminate Architecture, not Growth and Change, and says, "American readers may think indeterminate principle as unconstrained by the limitations of a program that has no basis in reality with respect to the lifespan of a project by feeling derogatory "ambiguity" or "unclear" in this phrase." It indicates a difference in attitudes between the U.S. and the U.K..

Ref. 223 devotes almost all of its "Overall Plan" section to explaining growth and change. Although Weeks is not mentioned, "The first method of effective planning for "growth" is to make and put extra space. The second method is to build a system of buildings in anticipation of future additions and alterations. It is very meaningful to treat the wing-tips as indeterminate, not as complete."

Yanagisawa227) discussed the relationship between facility management and growth and change. He mentioned Weeks, Indeterminate Architecture and Northwick Park Hospital, and pointed out that this kind of architectural response tends to be more about the hardware and less about the software with future changes in perspective. Facility management is also discussed in Ref. 233.

Ref. 228 is a revised version of Ref. 166. In the section "Responding to growth and change," the authors categorized the response methods into four types: Up-front investment type, Pavilion type, Equipment floors and Multi-wing type. Up-front investment type is a method that we can hardly imitate, such as building only structural frame. In the "Pavilion type" section, Weeks' Indeterminate Architecture and Northwick Park Hospital are discussed along with the layout plan, but "it may not be so easy to make up for the labor spent in coming and going through the corridor. I can't help but express my disapproval, as I feel that the daily burden is a bit too great for future growth." In terms of the "Equipment floors," "The question is whether it makes sense to allocate almost half the building's volume to equipments regarding construction costs. Such a question or criticism is quite big in the West as well. There have been a few cases in which it has been used only in departments where the need is greatest, and this may be a very effective method." The final section, "Multi-wing type," was explained in detail, using the examples of Chiba Cancer Center and Sundsvall Hospital in Sweden, as "a prima facie answer to the growth change in the current situation in Japan." In addition, growth and change appears in the index. The second edition229) evaluates "Equipment floor" as "this would be a clever choice because this would be a fairly effective method."

Ref. 230 is a commentary on Growth and Change by Weeks himself, which has already been introduced by Yanagisawa and others, so there is nothing new in this paper. However, as it includes a diagram of Ashmore Village, it is useful for deepening our understanding of the hospital's urban nature and its connection to Growth and Change.

Ref. 235 reviews the history of hospital architecture, citing examples from around the world. It begins, "In the U.K., the last architects grasping this situation were Davies and Weeks. They created a traditional indeterminate method. Their architectural principles allow for buildings that respond to orderly growth and gentle change." The authors explain the drawings for Northwick Park Hospital, but say that they are ineffective in urban areas by quoting Weeks' words, "What is really required is to design a building that is not best suited to a particular function, but at least does not interfere with the change in function." The index also includes growth and change.

Ref. 236 summarizes the history, design methods and examples by building type and presents Weeks, Growth and Change and Northwick Park Hospital.

Ref. 239 is an examination of Growth and Change by Weeks himself. Northwick Park Hospital has undergone a major change, with the private St. Marks Hospital taking over the site where the Clinical Research Centre left off. There was only one example of an open-ended extension and the rest were unexpectedly built on vacant land or even rooftops. There were also extensions that obstructed Hospital Street and unexpected parking lot extensions, but the site was large enough to continue to grow.

The site visit and verification by Yamashita241) also raised the issue of distance between central treatment department and emergency department extension built beyond hospital street, which was made due to the closure of emergency facilities in the surrounding area. The deputy chairman of the NHS Trust also noted that the Growth and Change was a symbol, but not an ideal one.

5 Conclusion

A survey of the literature shows that growth and change was noticed by Mori13) and theorized by Takamatsu31) before Weeks. Although there was a large amount of literature on growth and change before the introduction of Weeks, some of the earliest examples focused on building additions to prepare for the rapid increase of wounded and sick due to epidemics and war.

After WW2, the Yoshitake's Model Plan96,103,104,106) stated that sites for expansion should be prepared, and perhaps because of the presence of the Ministry of Health and Welfare in the background of their production, the idea of growth and change may have been popularized in various quarters of the medical community as well as architectural one. At the same time, Yoshitake and Ogawa's repeated and competitive translation of the U.S. design method for a general hospital that could be expanded87,102,118-121) may have had an impact.

During the rapid economic growth period, hospital design methods were becoming widespread and the concept of growth and change was becoming commonplace, but a specific methodology for how to design for future preparedness had not yet been found. That's when Weeks' Indeterminate Architecture jumped in. It turned out that it was Ito182) who first introduced Weeks to Japan in 1965, and Yanagisawa194) who wrote Growth and Change four years later. According to the interviews with Yanagisawa and Nagasawa, who both are Yoshitake's apprentices, Yoshitake at that time made them study Weeks, so there is no doubt that it was Yoshitake who brought Weeks to Japan. Growth and Change spread quickly after that, and despite some skepticism from Ito and Yanagisawa, the Chiba Cancer Center was accepted as an example of its application and success.

After the bubble economy period, the rebuilding of the old hospitals constructed right after WW2 were once completed, and a review of the growth and change began in preparation for the next rebuilding. However, when a POE of the Northwick Park Hospital was carried out, including by Weeks himself239), it became clear that it was not necessarily the case that Growth and Change had been achieved according to the ideal.

In the pre-war to mid-war period, post-war to reconstruction period, rapid economy growth period and bubble economy period and later, the percentages of articles describing growth and change and Growth and Change were 24.1%, 41.1%, 56.9% and 71.0% respectively, indicating that the impact of Weeks' work was significant. However, the "unavoidable relocation" of hospitals pointed out by Takeda68) is still common 80 years later, and the methodologies for vertical expansion, rejected by Osuga107) and Yoshitake166), have not yet been found. The aforementioned Figure 1 may be the basis for the consolidation of multiple hospitals and the reorganization of buildings promoted by the NHS in the U.K., but there may still be some lessons to be learned from Weeks in this small diagram.

References

All references are written in Japanese. They are listed in order of date of Publishing, but serials and minor revisions are listed consecutively. Following symbols have been added to the end of the references.

+ growth and change is mentioned, but no detailed explanation is given.

++ growth and change is explained in detail.

* Growth and Change is mentioned, but no detailed explanation is given.

** Growth and Change is explained in detail, but no mention of Ashmore Village.

*** Growth and Change is explained in detail and includes a description of Ashmore Village

No symbol: None of them are mentioned.

Pre-war to Mid-war Period (Before 1945), 20 papers with symbols out of 83

1) Nobuyoshi Tsuboi: Hospital Building Construction Law and Knowledge Requirements, Iji Zassi, (6), 1874.2+

2) Tadanao Ishiguro: History of the Halkenstein Lung Hospital, Chugai Igaku Shimpo, (77), 1883.5

3) Yuzuru Watanabe: Architectural Law for Medical Clinics, Kenchiku Zasshi, 1(1), 1887.1

4) Hanroku Yamaguchi: Outline of Construction of Sewerage Pipes for the First Clinic of Imperial University, Kenchiku Zasshi, 2(19), 1888.7

5) Rintaro Mori: Nursing of Wounded Soldiers, Army Medical Training Course, 1889.3

6) Rintaro Mori: Hospital, Eisei Shinshi, (4), (6), 1889.3, 1889.6

7) Heidelberg University New Hospital, Kenchiku Zasshi, 3(33), 1889.9

8) Rintaro Mori: New Sanatorium built with Medical Design, Eisei Shinshi, (15), 1890.2

9) Jiro Tsuboi: Ventilation volume of a hospital room, Kenchiku Zasshi, 4(45), 1890.9

10) Aisue T.Y.: Treatise on Hospital Architecture, Kenchiku Zasshi, 8(86), 1894.2

11) Kotaro Sakurai: Hospital Construction Law, Kenchiku Zasshi, 10(113), 1896.5

12) Rintaro Mori and Masanao Koike: Hygiene New Edition, Nanko-do, 1896.12

13) Rintaro Mori and Masanao Koike: Hospitals, Hygiene New Edition, 2nd edition, Nanko-do, 1899.5

14) Rintaro Mori and Masanao Koike: Hospitals, Hygiene New Edition, 3rd edition, Nanko-do, 1904.10+

15) Rintaro Mori and Masanao Koike: Hospital, Hygiene New Edition, 5th edition, Nanko-do, 1914.9+.

16) Keikichi Ishii: Theory of Hospital Architecture, Kenchiku Zasshi, 11(128), 1897.8+

17) Keikichi Ishii: Hospital Architecture, Kenchiku Zasshi, 12(138), 1898.6

18) Shunro Watanabe: Infectious Disease and Barracks, Kenchiku Zasshi, 19(225), 1905.9

19) Hoyo Okawa: Hospital Construction, Special Building Law Part 2-5, Kenchiku Sekai, 5(1)-(5), 1911.1-1911.5

20) Excerpt from the examination bylaws for an application for establishment of a private hospital (Metropolitan Police Department) and Extract from Regulations to Control Infectious Disease Units in Private Hospitals, Special Building Law, Vol. 9, Kenchiku Sekai, 5(8), 1911.8

21) Sei Nobukawa: On Hospital Architecture, Part I-13, The World of Architecture, 6(2), (4)-(7), (9)-(12), 7(2)-(4), 1912.2-1913.4

22) Naito: Early Modern German Hospital Architecture (1)-(4), Kenchiku Zasshi, 26(308), (309), (311), (312), 1912.8-1912.12

23) Shibasaburo Kitasato (ed.): Social education and curing pulmonary tuberculosis, 1913.7

24) Tokyo City Hospital Building Regulation Draft, Kenchiku Zasshi, 29(353), 1915.12

25) Outline of the present regulations for hospitals, Kenchiku Zasshi, 29(353), 1915.12

26) Tokyo City Hospital Building Regulation, Kenchiku Zasshi, 31(369), 1917.1

27) Department of Health, Ministry of the Interior: Summary of Tuberculosis Hospitals, Sanatoriums and Tuberculosis Prevention Society, March 1919.

28) ST: A few thoughts on hospital construction (1), Architecture and Society, 5(4), 1922.4

29) Akira Uenami: Solar radiation in and around hospital buildings, Kenchiku Zasshi,

36(430), 1922.5

30) A reporter: Osaka Municipal Hospital to begin construction, Architecture and Society, 6(5), 1923.5

31) Masao Takamatsu: On the construction of hospital, The Journal of Medical Science and Devices, 1(5), (6), 1923.9, 1923.12

32) Masao Takamatsu: Ideal Hospital Architecture, New Tokyo and Architecture, Jiji-Shimpo-Sha, 1924

33) Takehira Okado: Hospital architecture Miscellaneous Impressions: Orders from patients, Architecture and Society, 8(7), 1925.7

34) Kemehisa Obata: Wish to be in hospital architecture, Architecture and Society, 8(8), 1925.8

35) Sukehachi Nagane: Study of Hospital Architecture, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 1(1), 1925.9

36) E. F. Stevens: Design of a Hospital, Ika Kikaigaku Zasshi, 3(4), 1925.10

37) Mitsugu Yoshida: Hospital architecture, ARS Architecture, vol. 3, Arusu, 1926-1930+

38) Shogo Sakurai: On the Pharmacy Room in the Hospital, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(2), 1927.2

39) Shogo Sakurai: On the Bathroom Facilities of Hospital, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(3), 1927.3

40) Gennosuke Osawa: On the X-ray House, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(4), 1927.4

41) Shogo Sakurai: On the Operating Room, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(4), 1927.4

42) Sotusaburo Yamamoto: Psychological condition of the sick and miscellaneous impressions of hospital architecture, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(4), 1927.4

43) Keisuke Murao: A review of tuberculosis sanatorium architecture, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(4), April 1927.

44) Its Masuda: Construction requirements for hospitals, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(5), 1927.5+

45) Ichiro Osawa: An Introduction to the Mechanical Equipment of Hospitals, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(5), 1927.5+

46) Shogo Sakurai: On the Operating Room, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(5), 1927.5

47) Toshiro Ichimori: On artificial lighting in hospitals, Kokusai Kenchiku Jiron, 3(5), 1927.5

48) Masao Takamatsu: On the architecture of hospitals, Ika Kikaigaku Zasshi, 5(1), (2), 1927.7, 1927.8

49) MT: Recent progress in overseas hospital planning, Nippon Kenchikushi, 1927.8

50) Chinosuke Yamada and Seiichiro Yamazaki: The Latest in Medical and Hospital Architecture and Design, Kanehara Shoten, 1927.9

51) Seiichiro Yamazaki: Latest Medical and Hospital Architecture and Design, 6th edition, Kanehara Shouten, 1935.1

52) Ichiro Osawa: Outline of Mechanical Equipment of Hospitals (2), The International Journal of Architecture, 4(1), 1928.1

53) Juro Kondo: The basic concept of hospital planning, Kenchiku Zasshi, 42(514), 1928.10

54) MT: Fire in hospitals and the building structure of special hospitals, Nippon Kenchikushi, 4(3), 1929.3

55) MT: Hospital facilities and their preparation, Nippon Kenchikushi, 4(4), 1929.4

56) MT: Lighting in hospitals, Nippon Kenchikushi, 4(5), 1929.5

57) Juro Kondo: Hospital architecture, The Pocket Book of Architectural Engineering, Maruzen, 1929.7

58) Juro Kondo: Hospital architecture, The Pocket Book of Architectural Engineering, Maruzen, 1933.5

59) Juro Kondo: Hospital architecture, The Pocket Book of Architectural Engineering, Revised edition, Maruzen, 1949.1

60) Juro Kondo: On the architecture of Tokyo Doai Memorial Hospital, Kenchiku Zasshi, 43(525), 1929.9

61) MT: Protection against radiation in the planning of the hospital's X-ray department, Nippon Kenchikushi, 5(5), 1929.11

62) MT: Trends in hospital construction lately, Nippon Kenchikushi, 5(5), 1929.11+

63) Gennosuke Osawa: Hospital and Clinic Construction and Their Equipments, Homeido Shoten, 1931.5+

64) Gennosuke Osawa: Hospital and Clinic Construction and Their Equipments, 3rd edition, Homeido Shoten, 1941.8+

65) Masao Takamatsu: Modern Western hospital architecture through "Nosokomeion," Kenchiku Zasshi, 46(565), 1932.12

66) Masao Takamatsu: Hospital, Higher School of Architecture Vol.15 Hotel, Hospital and Sanatorium, Tokiwa Shobo, 1933.5

67) Masao Takamatsu and Tomiya Ibona: Hospital Architecture (Building Section), (Equipment Section), Pamphlet of Architectural Institute of Japan, 5(7), 1933.5+

68) Goichi Takeda: Modern tendency of hospital architecture, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10+

69) Saburo Kajiwara: A study of hospital architecture, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10

70) Kuro Washio: Tendency towards private rooms, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10

71) Saburo Okura: Some Problems in Hospital Architecture, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10

72) Ichiro Osawa: Hospital architecture and its mechanical facilities, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10

73) Kenzaburo Kumagai: On the architecture of special hospitals, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10

74) Masujiro Kinoshita: The characteristics and special facilities of Konan Hospital, Architecture and Society, 17(10), 1934.10

75) Tokio Mito: A few findings on the construction of tuberculosis sanatorium, Tuberculosis 13(6), 1935.6+

76) On the architecture of hospital, Masao Takamatsu's work and writings, Masao Takamatsu's memorial work, Sep. 1935.

77) shosaku Hariya: The present situation of tuberculosis sanatoriums in Japan, Kenchiku Zasshi, 51(624), 1937.3+.

78) Shujiro Haruki: Problems in the construction of tuberculosis sanatorium, Tuberculosis, 16(6), 1938.6

79) Jun Yamada: Study on hospital architecture and block plan, Hospital, Vol. 18, No. 5 (206), 1941.5

80) Kunitaro Ochiai: A study of the design of a hospital room for infectious diseases, The Hospital, No. 19(214), 1942.1+.

81) Outline of Construction of Japan Medical Unity Nuclear Sanatorium, Hospital, No.20(228), 1943.3

82) Ikuji Nishio: Equipment of university hospital seen from a clerical point of view, Hospital, No. 20(235), 1943.10

83) Shigeo Kono: Facilities of Japan Medical Center, Kenchiku Zasshi, 58(709), 1944.5+.

Post-war to Reconstruction Period (1945-1959), 30 papers with symbols out of 73

84) Hideto Kishida: On hospital architecture, Medical Care, 3(3), 1948.3

85) Fuminori Honna: Institutional facilities for patients, Medical treatment, 3(3), 1948.3

86) Seijiro Iwai: Institutional facilities for staff, Medical care, 3(3), 1948.3

87) Hospitals in the Chain System (1)-(5), Kenchiku Bunka, (27)-(31), 1949.2-1949.6

88) Tani: Japan's first Western-style hospital, The Hospital, 1(1), 1949.7

89) Yasumi Yoshitake: On the design of foreign hospitals, Hospitals, 1(2), 1949.8+

90) Eiichiro Hisamatsu: Visiting record of Center Hospital, Hospital, 1(2), 1949.8

91) Shintaro Kotani: Medical Treatment and Medical Institutions in the U.S.A. (1), (2), (3), Hospital, 1(4), (5), 1949.10, 1949.11

92) Y. Y.: A Brief History of Hospitals (No.1)-(No.19), Hospitals, 1(4)-6(6), 1949.10-1951.6

93) Senji Kobayashi: Hospital Architecture in Japan (1)-(4), Hospitals, 2(1), (3), (4), 3(1), 1950.1, 1950.3, 1950.4, 1950.7

94) Shintaro Kotani: Tuberculosis Hospital in the U.S., Hospital, 2(2), 1950.2

95) Fuminori Honna: About a few hospitals, Hospitals, 2(2), 1950.2

96) Ministry of Health and Welfare, Bureau of Medical Affairs: Outline of hospital site selection and construction plan, Hospital, 3(1), 1950.7

97) Building Research Institute: Collection of Model Building Drawings, Building Research Institute, 1950.10

98) Ryutaro Azuma: Minimum Standards for Hospitals in America, Hospitals, 4(1), 1951.1

99) Ministry of Health and Welfare, Health Bureau: Standard design of national health insurance clinics, National Health Insurance Research Committee, 1951.1+

100) Yasumi Yoshitake: On the design plan of hospital architecture, Kenchiku Zasshi, 66(771), 1951.2

101) AIJ (ed.): Architectural Design Materials Collection 2, Maruzen, 1951.2+

102) Translated by Eiichi Imamura, Takefumi Shimauchi: Elements of the General Hospital, Hospital, 4(3), (5), 5(1), (2), (5), (5), (6), 6(1), (2), (3), 1951.3-1952.3

103) Yasumi Yoshitake, Hiroshi Moriya, Yukio Yoshida: On the design of a 200-bed hospital, Hospital, 4(4), 1951.4+.

104) Hidetoshi Kishida, Yasui Yoshitake and Molin Kuo: Design of a General Hospital, Research Report of the Architectural Institute of Japan, 1951.5

105) Tuberculosis Prevention Division, Public Health Bureau, Ministry of Health and Welfare: A guide to tuberculosis sanatorium construction, Hospital, 4(6), 1951.6+

106) Junzo Sakakida: Guide to design of hospital buildings, Relief, (282), 1951.6+

107) Yanagi Osuga: Divisional architecture of the Small and Medium City General Hospital (1), (2), Hospitals, 5(2), (5), 1951.8, 1951.11++

108) Shigebumi Suzuki and Shunsuke Yamamoto: Hospital Design in Europe and America in 2.3, (13), 1951.8

109) Gennosuke Osawa: Architectural Drawings of Hospitals, Shokokusha, 1951.10

110) Gennosuke Osawa: Architectural Drawings of Hospitals, Revised and 10th Edition, Shokokusha, 1967.2

111) Shinichi Sekine: On the construction of a psychiatric hospital, Hospital, 6(1), 1952.1

112) Yasumi Yoshitake: On the Conditions for Designing a Ward and the Handling of Ward Blocks Two Problems of Ward Design in Japan, Kenchiku Bunka, (63), 1952.2

113) Yasumi Yoshitake: Report on Hospital Design in London Architectural Research Council (England, USA and Sweden), Kenchiku Zasshi, 67(784), 1952.3+

114) Shinichi Sekine: Management of Mental Hospitals, Hospital Encyclopedia 2, Igaku-shoin, 1952.8

115) Gennosuke Osawa: Planning of Medical Hospital Construction, Shokokusha, 1952.10+

116) Fuminori Honna: Equipment of Hospitals, Hospitals, 3, Igaku-shoin, 1952.10

117) Fuminori Honna: Progress of Hospitals, Hospitals, 7(4), 1952.10+

118) Takehiko Ogawa: Design and Structure of the General Hospital (1)-(10), Hospital, 7(5)-9(3), 1952.11-1953.9+

119) Takehiko Ogawa: Hospital Architecture Planning and Equipment, Shokokusha, 1955.9+

120) U.S. Department of Education and Health Sciences, Public Health Service (ed.), translated by Yasumi Yoshitake, Gentaro Watanabe, Makoto Ito: Design and Structure of the General Hospital, Sagami Shobo, 1956.11

121) U.S. Department of Education and Health Services, Public Health Service (ed.): Design and Structure of General Hospitals, revised edition, Sagami Shobo, June 1968

122) Committee of University Hospitals: Guidelines for improving University Hospitals, Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Monthly Report, 1953.1

123) Takashi Takano: Planning of General Hospital, Architectural Technology, (25), 1953.6

124) Kisaburo Ito: Department and Space of Modern Hospitals, Shinkenchiku, 28(10), 1953.10+

125) Ichiro Suzuki: On hospital planning, Kenchiku Bunka, (83), 1953.10

126) Yasumi Yoshitake: Central Clinic Facilities of Hospital, Kenchiku Bunka, (87), 1954.2

127) Hitoshi Hoshino: Renovation of a Medical Hospital and Design of an Infirmary, Kanehara Publishing, 1954.10

128) Hirotoshi Hashimoto and Kenichi Takino: Outpatient Care in Hospitals, Equipment and Function of Hospitals in Perspective 11, 1955.1

129) Hideya Kobayashi: Perspectives on the Construction Plan of University Hospital (1)-(5), Hospitals, 12(5), 13(1)-(4), 1955.5-1955.10+

130) Hirotoshi Hashimoto: Equipment and Functions of Modern Hospitals with Photographs, Hospital Encyclopedia 8, Igaku-shoin, June 1955.

131) Hideo Kunikata and Masataka Tanaka: The medical ward of Kanto General Hospital, Kenchiku Bunka, (104), 1955.7

132) Mamoru Yamada: Block plan of the General Hospital to which I was connected, Kenchiku Bunka, (104), 1955.7

133) A Study of the General Hospital Plan (Architectural Record), Kenchiku Bunka, (104), 1955.7

134) Yasumi Yoshitake: Planning of Hospital Outpatient Department, Kenchiku Bunka, (104), 1955.7

135) Planning of a hospital starts from the flow line, Kenchiku Bunka, (104), 1955.7

136) Special Issue on Hospital Architecture, Kenchiku Sekai, 5(4), 1956.4

137) Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.): Handbook of Architecture, Maruzen, 1956.12

138) Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.): Handbook of Architecture, 2nd edition,

Maruzen, 1959.1+

139) Yasumi Yoshitake: Recent developments in hospital architecture, HOSPITALS, 16(2), 1957.2+

140) Takefumi Shimauchi: Hospital Management, Byoin Zensho 10, Igaku-shoin, 1957.3+

141) Takefumi Shimauchi: Hospital Administration, 2nd edition, Igaku-shoin, 1967.10

142) Takashi Hirayama, Kunio Maekawa, Yasumi Yoshitake et al.: Shinsei Kenchiku Keikaku, 1957.4+

143) Makoto Ito: Some Problems of Hospital Architecture in Modern Japan, Shinkenchiku, 32(5), 1957.5+

144) Yasumi Yoshitake: Recent developments in hospital architecture, Shinkenchiku, 32(5), 1957.5+

145) Eiichi Imamura: The reality of hospital management, Igaku-shoin, 1958.4+

146) Yasumi Yoshitake: Hospitals in England and Germany, The Hospital, 17(6), 1958.5

147) Takehiko Ogawa: Hospital architecture in Europe, Hospitals, 17(6), 1958.5

148) Shogo Sakurai: Building Facilities of Hospitals in Europe, Hospitals, 17(6), 1958.5

149) Yasumi Yoshitake and Takehiko Ogawa: Graph of European Hospital Architecture, Hospitals, 17(6), 1958.5

150) Tokutaro Nishijima: Attendance at the first International Hospital Architecture Seminar, Hospitals, 17(6), 1958.5

151) Hiroshi Moriya, Takehiko Ogawa, Shogo Sakurai, Yukio Yoshida, Yasumi Yoshitake, Hospital Architecture in Europe, Hospitals, 17(6), 1958.5

152) Takehiko Ogawa: Hospital Architecture in Europe, Shokokusha, 1959.3

153) Yasumi Yoshitake and Makoto Ito: On recent medical facilities, Architecture and Society, 40(10), 1959.10

154) Ryoichi Ura: A proposal for a future medical and health care facility network (A proposal for a large housing complex), Architecture and Society, 40(10), 1959.10

155) Makoto Ito and Kaichiro Kurihara: On the type and size of nursing units, Architecture and Society, 40(10), 1959.10

156) Rurushige Miura: A critical look at hospital architecture, Architecture and Society, 40(10), 1959.10+

Rapid Economy Growth Period (1960-1979), 33 papers with symbols out of 58

157) Yasumi Yoshitake: Tokoname City Hospital, Kenchiku Bunka, (159), 1960.1

158) Shingo Kawamura: Problems in Hospital Facilities, Kenchiku Bunka, (159), 1960.1

159) Japan Institute of Hospital Architecture (ed.): Illustrations of Hospital Architecture in Japan, Shokokusha, 1960.2+

160) Yasumi Yoshitake, et al.: A Study on Architectural Planning of Hospitals, Annual Report of the Architectural Institute of Japan, 1960.7

161) Yasumi Yoshitake: Hospital Architecture and Its Functions, The Complete Collection of World Architecture 12, Modern III: Bunka To Kosei, Heibonsha, 1960.8

162) Yoshitake Laboratory: Architectural Planning Note (2), Shokokusha, 1960.9

163) Kenji Danno, Yasumi Yoshitake, Shogo Sakurai: Architecture and Facilities of Hospital, Problems of Hospital Architecture and Facilities, Hospital, 19(9), 1960.9

164) Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.): Architectural Design Materials Collection 2, Maruzen, 1960.12

165) Yasumi Yoshitake et al.: The University of Architecture <35> Hospital, Shokokusha,

1962.6+

166) Yasumi Yoshitake et al.: The Newly Revised College of Architecture <35> Hospitals, Shokokokusha, 1969.3+

167) Yasumi Yoshitake: The trend of hospital architecture and future problems, Hospitals, 21(10), 1962.10+.

168) Yasumi Yoshitake: Planning the Design of Hospitals Length of Stay and Design Planning, Mathematics Seminar, 2(7), 1963.7

169) Hospital Architecture Research Group (ed.): Hospital Function and Architecture, Science and Technology Library, Sept. 1963.

170) Hirotoshi Hashimoto: A Photographic Commentary on Hospital Management, Igaku-shoin, 1963.11

171) Yasumi Yoshitake: Hospital attached to the Cancer Institute, Kenchiku Bunka, (205), 1963.11

172) New Clinic/additional volume: Planning and design of clinic architecture, Physicians' Drug Publishing, 1964.1

173) Yasumi Yoshitake: On recent hospital architecture, Juntendo Medical Journal, 9(3/4)(634), 1964.3

174) Yasumi Yoshitake: Hospital architecture, Hospital, 23(6), 1964.6

175) Kisaburo Ito: Hospital architecture plan 1-6, Kenchiku Sekai, 13(10), (12), 14(1), (2),

15(7), (8), 1964.10-1966.8

176) Yasumi Yoshitake: Study on architectural planning Architectural planning on the usage of buildings, Kajima Publishing Company, 1964.12

177) Planning and Design of Medical Clinic Architecture Vol. 1, Medical and Dental Publishing, 1964.12

178) Planning and Design of Medical Clinic Architecture Vol. 2, Medical and Dental Publishing, 1965.2+

179) Planning and Design of Medical Clinic Architecture Vol. 3, Medical and Dental Publishing, 1967.5+

180) Hiroshi Moriya, Yasumi Yoshitake et al.: New Hospital Facilities, Ika Kikaigaku Zasshi, 35(1), 1965.1

181) Japan Institute of Hospital Architecture (ed.): Illustrations of Hospital Architecture in Japan, Shokokusha, April 1965.

182) Makoto Ito: The future of hospital architecture, Architecture and Society, 46(12), 1965.12

183) Nikken Sekkei Hospital Planning Study Group: From the perspective of an architect, Architecture and Society, 46(12), 1965.12+

184) Yasumi Yoshitake, Ryoichi Ura, Masao Hayakawa, Norio Nishino, Makoto Ito: Aichi Cancer Center, Shinkenchiku, 41(4), 1966.4

185) Yasumi Yoshitake: The design of rehabilitation facilities(2) Rehabilitation Center of the University of Tokyo Hospital, Hospital, 26(1), 1967.1+

186) Yasumi Yoshitake: Introduction to architectural planning (1), Corona, 1967.3+

187) Yasumi Yoshitake: Hospital architecture and ergonomics, Rinsho Kagaku, 3(6), 1967.6

188) Nikken Sekkei: Hospital Architecture, 1967.11

189) Takefumi Shimauchi: Hospital Administration, The Latest Nursing Encyclopedia, Special Volume 4, 1967.11+

190) Kiyonobu Mikanagi: Fundamentals of hospital architecture, Chiryo, 50(1), 1968.1

191) Hospital architecture (Kehiko Ogawa & Associates), Architecture, (94), 1968.6

192) Nikken Sekkei Hospital Planning Study Group: Hospital Design Theory, Architecture and Society, 49(6), 1968.6

193) Eiichi Imamura: Theory and practice of hospital management, Igaku-shoin, 1968.11+

194) Tadashi Yanagisawa: Growth and change in hospital architecture, Journal of Contemporary Medicine, 17(1), 1969.9**++

195) Tota Nomura: The present situation and new direction of medical facilities in Europe and America-1, Kenchiku Bunka, (277), 1969.11+

196) Tadashi Yanagisawa and Shoji Imai: Designing for Growth and Change: A New Approach to Hospital Architecture, Kenchiku Bunka, (278), 1969.12**++

197) Makoto Ito: Hospitals, Architectural Planning 10, Maruzen, 1970.7+

198) Ryoichi Ura et al.: Medical Care, Architectural Planning 4: Community Facilities, Maruzen, June 1973.

199) Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.): A History of the Development of Japanese Architecture, Maruzen, 1972.9

200) Tadashi Yanagisawa: McMaster University Health Science Center, Hospital Architecture, (17), 1972.10*++

201) Makoto Ito: Hospital architecture and ward equipment, Ika Kikaigaku Zasshi, 43(9), September 1973.

202) Makoto Ito et al. ed: Building, Equipment and Medical Devices, Hospital Administration Series, Volume 6, II, Igaku-shoin, 1974.1++

203) Yasumi Yoshitake: Introduction to Hospital Design Planning, The College of Modern Surgery 1, Nakayama Shoten, 1974.12+

204) Nikken Sekkei: Hospital Architecture, Nikken Sekkei, 1975++

205) Tadashi Yanagisawa: Medical equipment from the viewpoint of hospital architecture, Ika Kikaigaku Zasshi, 45(11), 1975.11++

206) Katsuhiro Hayashi: Hospital Architecture from the Viewpoint of Medical Equipment, Journal of Medical Instrumentation, 45(11), 1975.11+

207) Sadamitsu Masuda: Hospital Architecture from the viewpoint of Medical Equipment -Focusing on the wall system of ICU and CCU-, Journal of Medical Instrument Science, 45(11), 1975.11

208) Japan Institute of Hospital Architecture (ed.): Illustrations of Hospital Architecture in Japan, Kajima Institute of Technology, 1976.4+

209) Special Issue on Hospital Architecture, Kenchiku Gaho, 12(108), 1976.11++

210) Yasumi Yoshitake: Hospital architecture in the future, Hospital, 38(1), 1979.1

211) Takehiko Ogawa: Structure of hospital architecture, Kajima Institute of Technology,

1979.8+

212) Takehiko Ogawa: Structure of hospital architecture, Kashima Institute, 1987.12+

213) Takehiko Ogawa: A method of hospital formation for planning and design practice, Kajima Publishing House, 2000.5++

214) Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.): Architectural Design Materials Collection 6 Architecture-Life, Maruzen, 1979.10+

Bubble Economy Period and Later (1980-2004), 22 papers with symbols out of 31

215) Kajima Corporation Architectural Design Division: Hospitals As a guide for those who build, 1980++

216) AIJ (ed.): Handbook of Architecture I, Planning, 2nd edition, Maruzen, 1980.2++

217) Kensetsu Kogyo Chosaikai: Base Design Document for Hospital Facilities, Kensetsu Kogyo Chosaikai, 1980.4+

218) Yasumi Yoshitake: Introduction to Hospital Construction Planning, Hospital Management System Volume 6, I, Igaku-shoin, 1980.11++

219) New Japan Institute of Architects (ed.): Medical Hospital I: Private Clinic, Shokokusha, 1983.12

220) New Japan Institute of Architects (ed.): Medical Hospital II: Private Hospital, Shokokusha, 1984.5

221) S. Nagel + S. Reinke, translated by Katsuo Komuro: Hospitals, Special Hospitals, World Architecture Photo Series 12: Medical Facilities, Shubunsha, 1984.2+

222) Lewis G. Redstone (ed.), translated by Kazuo Tanaka: Hospitals and Medical Facilities, Contemporary Architecture, 1984.11**++

223) Kenchiku Shicho Kenkyusho Kenkyusho (ed.): Hospital Architectural Design Materials 11, Architectural Materials Research Co.

224) Medical Clinic Planning Editorial Committee (ed.): Examples of Hospital Planning and Design, Shokokusha, 1986.7+

225) Medical Clinic Planning Editorial Committee (ed.): Examples of medical clinic planning and design, Revised edition, Shokokusha, 1997.12

226) Japan Hospital Architecture Association (ed.): Architectural drawings of modern Japanese hospitals, Kajima Publishing, 1986.11+

227) Tadashi Yanagisawa: Growth, Change and Facility Management, Hospital Facilities, 29(4), 1987.7*++

228) Makoto Ito et al.: Shin Kenchiku Taikei <31> Hospital Design, Shokokokusha, 1987.9**++

229) Makoto Ito et al.: Shin Kenchiku Taikei <31> HOSPITAL DESIGN, 2nd edition, Shokokusha, 2000.8**++

230) J. Weeks, translated by Yasushi Nagasawa: Geography of Hospitals, Hospitals, 46(11), 1987.11***

231) Choichi Shinya: A Historical Study of Hospital Architecture in Modern Japan, Kyushu University, 1988.2

232) Yasumi Yoshitake: The process of making a model plan for a general hospital (1950), Proceedings of Kanto Branch of Architectural Institute of Japan, (59), 1989.11

233) Saburo Kamibayashi: Handbook of Hospital Facilities, Japan Planning Center, Nov. 1989

234) Robert Visscher, translated by Hille Lau and Katsuo Komuro: New Challenges in Hospital Architecture: The Coming of the Age of All Private Rooms, Shubunsha, 1990.12

235) W. Paul James, William Tatton-Brown, Yutaka Kawaguchi, translated by Midori Nomura: Hospitals: The Development of Hospital Architecture, Planning and Design, Soft Science, 1992.2+**

236) S.D.S. Editorial Board: S.D.S. Space Design Series Volume 4: Medical and Welfare, New Japan Hoki Publishing, 1995.7**++

237) Sumio Fujie et al.: Architectural Planning and Design Series 16 Health Care Facility, Ichigaya Press, 1999.8++

238) Kenchiku-Shicho Kenkyusho Kenkyusho (ed.): HOSPITAL 2: Architectural Design Document 72, Architectural Materials Research Co.

239) J. Weeks, translated by Yasushi Nagasawa: Can hospitals cope with growth and change? Validation at Northwick Park Hospital, Hospital, 59(9), 2000.9++**

240) Architectural Institute of Japan (ed.): Architectural Design Documents: Welfare and Medical Care, Maruzen, 2002.9+

241) Tetsuro Yamashita: Verification of Growth and Change of hospitals, Hospitals, 62(4), 2003.4++**

242) Jun Ueno et al.: A study of the planning history of hospital architecture in post-war Japan, Japan Health and Welfare Architecture Association, 2004.6+

243) Yasumi Yoshitake: Brief Description of Architectural Design Studies I, 2004.11

244) Yasumi Yoshitake: A Brief History of Architectural Design Studies II, Nov. 2004.

245) Yoon Seowon: A Study on Formal Standards in Japanese Modern Hospital Architecture, University of Tokyo, March 2007.

Send by e-mail: