Publications IPH Magazine Revista IPH Nº17 Healthcare closer to people: A qualitative study of a Swedish reform on healthcare delivery

- IPH Magazine #17

- COVID-19 pandemic and the trends in healthcare design: insights from the "Decalogue for Resilient Hospitals"

- Healthcare closer to people: A qualitative study of a Swedish reform on healthcare delivery

- Spatial flexibility and extensibility in hospitals designed by João Filgueiras Lima

- Design Insights from a Research Initiative on Ambulatory Surgery Operating Rooms in the U.S.

- A study on the development of the concept growth and change on hospital architecture in Japan

- A study on hospital infection control through architecture in 1980: Chapecó Regional Hospital case study

- Natural ventilation for hospitalization environments: historical aspects

- Hospital architecture and its propositions for beginners and experts

Healthcare closer to people: A qualitative study of a Swedish reform on healthcare delivery

Erika Eriksson, Göran Lindahl, Patrik Alexandersson, Sofia Park and Henrike Almgren - Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to explore the considerations and potential effects of moving healthcare closer to people by drawing from the planning process of a regional initiative to establish two local hospitals in Sweden. Three main dimensions were identified: (i) closeness; (ii) collaboration, (iii) citizen and patient involvement. The interconnectedness among the three main dimensions was found to be important for understanding the new landscape resulting of the Swedish reform of "healthcare closer to people." An inductive approach was applied utilizing the Gioia methodology and member-validation, this guided the qualitative analysis of, mainly, focus group and individual interviews. The paper's states that a multiplicity of perspectives needs to be taken into consideration for successful reforms within contemporary healthcare and hereby it also aim to contribute to the discussion on the reform.

Keywords Public sector reforms, Healthcare, Patient engagement, Decentralization, Patient centeredness, Sweden,

Introduction

In the decentralized Swedish healthcare system, the national government is responsible to legislate and to establish principles and guidelines (SKR, 2018). Like in other countries (Ferrario and Zanardi, 2011), the national level may to certain extent equalize geographical differences. The 21 regions are responsible for providing healthcare, most commonly through primary care and specialized care at often large hospitals (SFS, 2017). Within the regional healthcare systems and hospitals, separate units have been increasingly decentralized, including also planning and accountability, over the last decades (Andersson and Liff, 2012). Since a reform in 1992, the 290 municipalities are responsible for providing care at home or at special accommodations with added service or support, not least for older patients (SOU, 2016). Despite relatively good clinical results (Coleman et al., 2011; MacDorman et al., 2014), lacking patient involvement is one of the challenges for the Swedish healthcare system (Vårdanalys, 2014) as is fragmentation (Eriksson et al., 2020) and escalating costs (SOU, 2016). These challenges call for a transformation of the system, not least by moving healthcare closer to people.

The national inquiry Efficient Healthcare (SOU, 2016) problematizes the Swedish healthcare system's focus on large hospitals. As an extension, another inquiry (SOU, 2019a) was launched, putting focus on the need to move resources from large hospitals (often distant in the sparsely populated parts of Sweden) to the geographically closer primary care and care for which the municipalities are responsible, but also to increase accessibility by, for example, improve use of information technology. Digitalization is also argued to enable task-shifting from staff to patients (Nordgren, 2009; SKR, 2019a), which also is likely to move healthcare from large hospitals to local level, even to patients' homes (SKR, 2019b). The direction of future healthcare has also been suggested to increase focus on health promotion and disease prevention, rather than today's focus on curing (mainly acute, time-critical) diseases at large, and expensive, hospitals (SOU, 2016, 2019a).

The need to reform the Swedish healthcare system should be understood in light also of the aging population structure (Socialstyrelsen, 2013) entailing that more people are living with multiple and chronic diseases today which, in turn, has brought to surface severe coordination problems among the various care providers these patients are likely to have in a decentralized system (Eriksson et al., 2020). At the same time, policy in the healthcare system, the caring, is changing towards person-centered care, entailing increased focus on patient integrity, individual control and safety as well as lowering barriers between the healthcare system and patients (Alharbi et al., 2012; Morgan and Yoder, 2012). Naturally, such policy will have consequences for both healthcare processes and the location and function of facilities used. All of the above reports, inquiries and trends are collectively supporting the current development of the Swedish reform of "healthcare closer to people." It is an ongoing work with an aim to restructure the healthcare in Sweden with an emphasis on care responding quicker to peoples need on a local level and at the same time allow for centralized specialization concerning more complex treatments. It also involves integration of regional and municipal care, home care and addressing issues related to the demographic situation, i.e. an ageing population. This development is a both a condition and a backdrop to the present case of the paper.

In parallel to the above-mentioned reforms, there is a booming construction of new healthcare facilities in Sweden. Because of an ageing building stock, new technologies, and new environmental requirements, Sweden invests approximately 10 billion euros over the years 2010-2020 (SKR, 2020). With the regionalized responsibilities each region updates and refurbish their healthcare building stock, mostly independently of each other. In urban areas the hospital areas are also reconceptualized as a part of the urban grid rather than an enclosed area for staff and patients only. Added to this should also be all the future adaptations of homes and public buildings that will be the result of the work concerning close care

In the regional context, decentralization of resources from large hospitals to smaller hospitals, focusing on local context, is important in the current transformation as it is perceived to increase efficiency, accessibility, equality and patient-centeredness (VGR, 2017). In light of the previous paragraph, this and similar reforms need to be understood as embeddedness in social context characterized by a multiplicity of perspectives and overlapping discourses that reveal that achieving wanted outcomes by bringing healthcare closer to people is not a matter of course. The purpose of this paper is to contribute with knowledge that can be used to increase understanding of the process of establishing local hospitals, healthcare systems and, more generally, decentralized public services.

Literature review

Decentralization

The last decades, the development in many western countries has been towards decentralization of public healthcare resources and authority (Anton et al., 2014; Magnussen et al., 2007; Saltman, 2008). The objective being to achieve efficiency and connect to local contexts. Definition of decentralization is not a matter of course, not least because it may be differently defined within the overlapping fields of management studies, organizational theory, public administration, and political science (Dubois and Fattore, 2009; Park, 2013; Pollitt, 2005). However, a commonality is that decentralization tends to focus on either spatial dimensions or organizational dimensions (Peckham et al., 2008). Influences from private sector the last decades have reinforced decentralization by moving resources from central to regional/local governments, focusing on facilities' local contexts rather than large and centralized institutions (Alonso et al., 2015; Pettersen, 2001) and by promoting decision-making and accountability at lower levels within public organizations (Mattei, 2006; Fransson and Quist, 2014). Some of the benefits of decentralization include increased democracy, accessibility, innovation, and efficiency (Madon et al., 2010; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Peckham et al., 2008; Saltman et al., 2006). In a healthcare context it is argued that the alignment with the local community increases ease and flexibility in designing and improving services as well as being a prerequisite in addressing health promotion and disease prevention (Heaney et al., 2006; Park et al., 2013). The arguments against decentralization in healthcare include that volumes may be too small to develop knowledge and skills of certain illnesses which may lead to poor clinical quality (Learn and Bach, 2010; Wouters et al., 2009), inefficiency, and costly services (Banzon and Mailfert, 2018). Contrary, centralization to, for instance, large hospitals would guarantee enough volumes to carry out complex procedures (Versteeg et al., 2018), which in turn would justify investments in top-of-the-line technology and enable research to be conducted (Gatta et al., 2017; Weitz et al., 2004). Indeed, it is argued that re-centralization is occurring in some healthcare systems (Gauld, 2012; Mauro et al., 2017), including those in the present paper's neighboring countries of Denmark (Christiansen and Vrangbæk, 2018) and Norway (Adam et al., 2019).

Multiplicity of logics in healthcare

It is important to note that official reports (e.g. Socialstyrelsen, 2003) that have emphasized healthcare closer to people previously to the aforementioned, already noted that these were "not new at all but rather the same principles that had been suggested [...] in the early 1970s" (Anell et al., 2019, p. 110). If this reform is not new, how come healthcare has still not established itself according to these principles or moved closer to people?

One answer may be the complexity of healthcare organizations and systems (Batalden and Davidoff, 2007; Berwick, 2008). The presence of a multiplicity of professions housing a variety of knowledge interests from various disciplines (Bergman et al., 2015) complicates matters. Mintzberg (2017) identified different perspectives in healthcare that need to be united when changing healthcare organization: care and cure, referring to the nursing and medical professions; control, executed by managers; and community which is constituted by politicians and citizens. In a broader level of abstraction, the traditional discourse (Foucault, 1993) of medicine which regulates the role-casting between staff and patients (Gaventa and Cornwall, 2007) has been complemented by a managerial discourse emphasizing profitability and the active healthcare "customer" who is making choices (Nordgren, 2009; Malmmose, 2015). The overlap of these and other discourses - each regulating what can be said and done (and not) - and the multiplicity of professional perspectives (Mintzberg, 2017) impacts how contemporary healthcare is organized and managed as well as complicates healthcare improvements because the logics may be conflicting. To complicate things further, it is suggested that healthcare should not be understood in isolation, but rather as part of a broader welfare system which entails interconnectedness with other private, public and third sector actors - and additional logics (Fransson and Quist, 2014; Osborne, 2018).

Method

Setting

The present paper draws from a local single case (Ragin and Becker, 1992) of Swedish healthcare set in the Western Region of Sweden. This region is the second largest in Sweden and inhabits 1,7 of Sweden's 10 million inhabitants (Statistics Sweden, 2019). In this paper, we studied how officials in a project group working with the establishment of two local hospitals and other healthcare professionals, managers and politicians directly concerned by healthcare closer to people perceived key aspects of the reform. The benefit of qualitatively study one case thoroughly is to potentially generate findings that contribute to develop theory as well as sharing knowledge that may open up for future research, in other contexts (Carmona and Ezzamel, 2005).

Data collection

Data was primarily collected through two semi-structured focus group interviews (Morgan, 1996) with project group participants and six semi-structured individual interviews with other stakeholders, done by either of the paper's authors. Both groups were considered relevant due to their engagement, insight and knowledge of the project. Additional data was also collected from the project group, including observations and notes from meetings as well as reports and other documents related to the project, often these sources of data was a point of departure for interviews. Interview topics were also retrieved from key concepts and themes in international journals and national inquiries that the participant was asked to define and elaborate on ("local hospital", "health promotion", "close healthcare", etc.). Data was collected during the first phase of the project (2016-2018). From May 2019 a broader approach has been applied in the project, for example concerning citizen involvement which is further elaborated beneath.

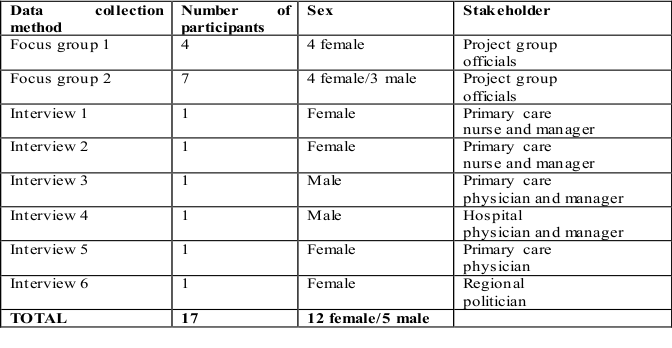

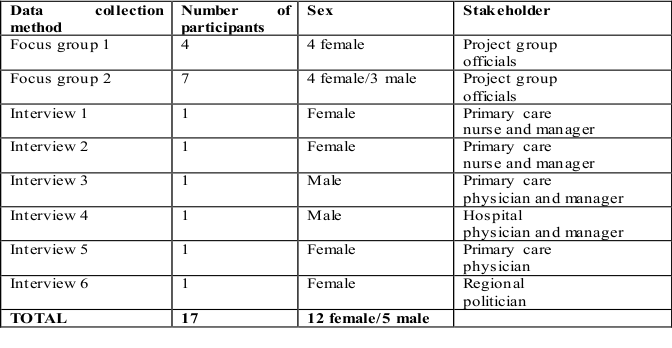

Table I. Data collection methods and participants

Data analysis

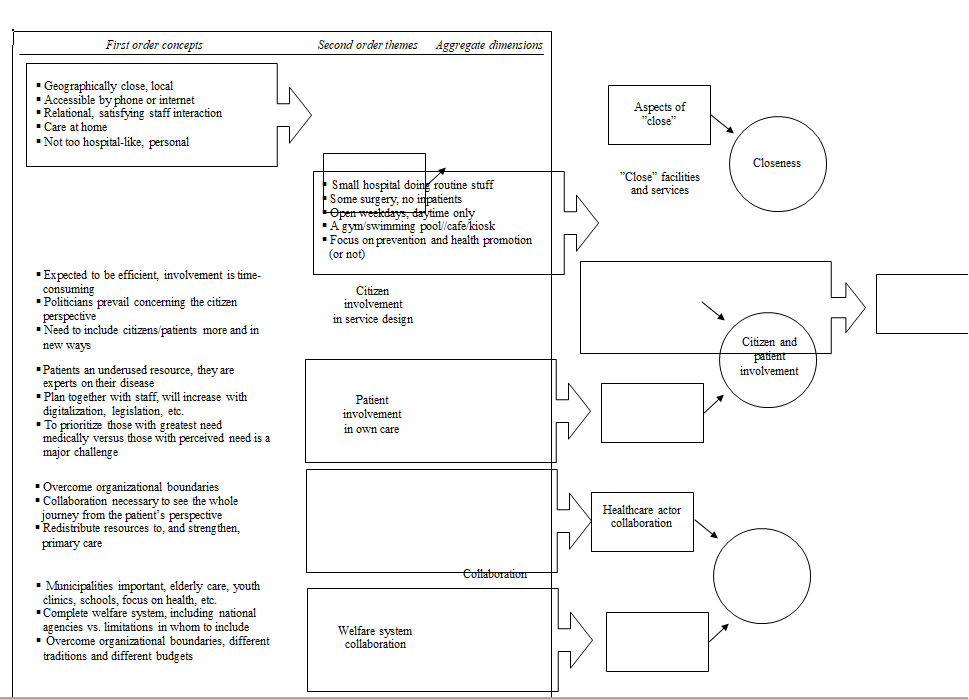

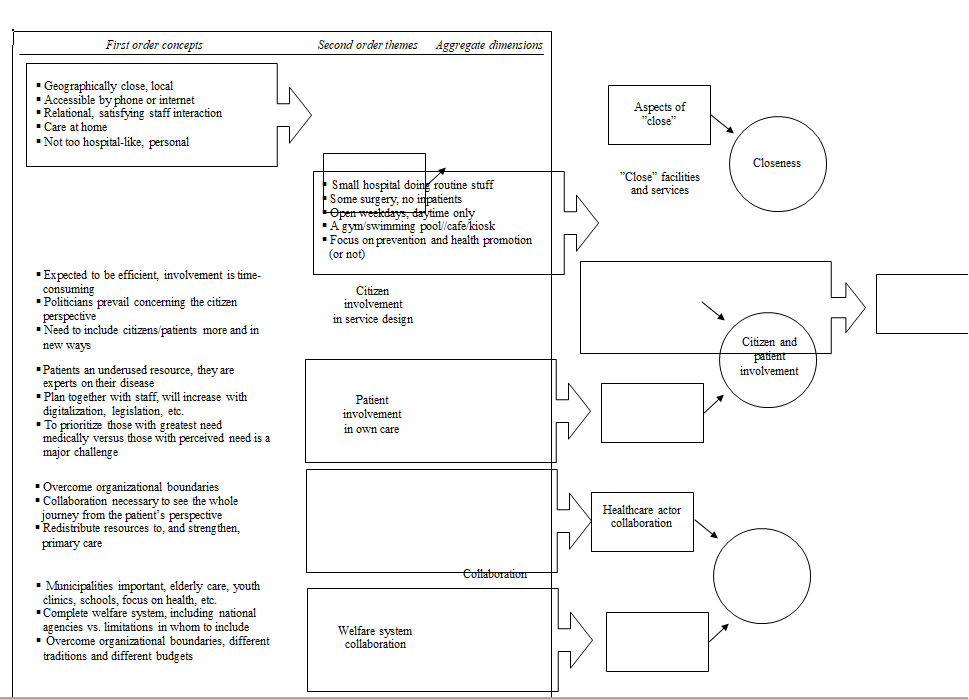

Based on an inductive coding procedure entailing a description of how coding is derived from findings (Corley and Gioia, 2004; Gioia et al., 2013), the collected data was sorted into first order concepts, second order themes and aggregate dimensions. In the analysis of the first order concepts we stayed as close as possible to the interviewees' answers, such as used vocabulary, expressions etc. Here, their interpretations of aspects central in healthcare close to people was at the heart. The second order themes were constructed by us and based on similarities between first order concepts. A deviation from the procedure was done by discussing tentative second order themes with the project group members at a workshop with the purpose of letting them validate interview findings and that we had understood the context accurately as well as deepening understanding of the constructed themes (Greenwood and Levin, 2007; Lincoln and Guba, 1985). We returned to the standard procedure for the final step of developing overarching aggregate dimensions. Figure I illustrates the coding structure.

Figure I. Coding structure

Empirical findings

In this section we will revisit the aggregate dimensions closeness, citizen and patient involvement and collaboration, presented in the previous section, as well as illustrated in figure I.

Closeness

This aggregate dimension includes aspects related to "close" as well as expectations of these "close" facilities and services.

In the former, aspects of close, geographically close services were mentioned to be important in the local community. However, one interviewee doubted the feasibility of this aspect of closeness in the present project: "If you build two local hospitals in this city, how many of the one million inhabitants will really feel that it is close?" However, others argued that geographical closeness was not exclusive to the location where one lived, but also to people's jobs, leisure, and so forth. Despite a certain distance, "close" could be achieved through information technology in which the patient could be at home discussing issues with healthcare staff. Another aspect that also was mentioned as a notion of "close" was the relational aspect, and that closeness was experienced in the encounter with staff from the patient's perspective. Continuity in contacts was noted as an important aspect in order to establish such relationships, e.g. to meet the same staff if possible.

For the aspect of closeness focusing on facilities and services, it was argued that such "close" facilities and services should address the care often needed by an individual or among the local population. The local hospital should be smaller but still capable of offering various specialist services and outpatient clinics, including outpatient surgery. The association embedded in the name "local hospital" related it to the notion of a full/complete "hospital" and brought with it an obligation to provide, for example, diabetes specialists, something that would also separate them from primary care. However, it would indeed be possible to do what was described as "simple stuff" at the local hospital, such as checking

blood pressure.

Others thought the term "hospital" was misleading because people would expect an emergency department, something most of the interviewees would prefer not to have at local level. However, not to have inpatient clinics was something that many interviewees considered as relevant as opening hours would be restricted to weekdays and daytime. "Close facilities" would entail a natural meeting place in the local context that offered "a more holistic building in which other aspects [than healthcare] was integrated", for example training and meditation for staff and patients, daily activities for disabled and elderly, a gym or a café. Similarly, others suggested they would welcome a less "hospital-like" facility, a design with less of institutional character than common healthcare facilities.

As interviewees discussed what offerings the local care facility should have, many differing opinions about preventive care emerged. There were just as many of the interviewees that thought health promotion would be a particularly important issue to address for the local hospitals, as those rejecting the idea. Among the former, it was argued that healthcare needed to address the growing problems with obesity, smoking habits, and other life-style related problems. It was argued by the interviewees that this should be the local hospital's tasks not least because health and prevention was particularly important for already sick patients in order to prevent them from getting worse. The opponents commented that it was not the task for a hospital - large or small - but primary care and municipalities to inform citizens about health. Others argued that at the end of the day, this was the responsibility of citizens themselves, and that healthcare should mainly offer information for people to act upon. Moreover, there was no time to work with prevention and promotion since hospitals were not given any money for working with these issues: "You don't get any compensation for preventing disease." One interviewee was critical of this logic of medicine in which "to save someone" was more important than to prevent disease. Consequently, it was argued, resources in healthcare are distributed in accordance with this medical logic.

Citizen and patient involvement

The discussion of this aggregate dimension concerns citizen involvement in designing healthcare services as well as patient involvement in their own care.

With regard to citizen involvement, there was frustration from some of the project members who wanted to involve citizens in the discussions of the new local hospitals, but who had been informed that the politicians wanted to do that themselves. This caused worry because the experience was that "they [the politicians] talk in terms of numbers and figures" and that citizens would not be allowed to participate in genuine decision-making. A politician confirmed this situation by stating that initially all politicians wanted to involve citizens. However, instead they had meetings with city district officials, and members of the project group of the new hospitals. citizens were not represented at these meetings. Citizen involvement in this project was mainly a "paper product" one interviewee said. Despite the initial clear ambition from politicians - "They are elected by the people, so they argue that they represent people in a way" as mentioned by one interviewee - it was important to involve patients because they, as sick citizens, could have important perspectives that the elected politicians did not have. However, because they were allowed to involve neither citizens nor patients, it was as if the politicians "insinuate that citizens and patients in some way would be a barrier or obstacle in our process [...] we're supposed to be so darn efficient so there's no time to involve them [citizens and patients]". Others agreed, meaning it made it difficult to be innovative when not being allowed to involve citizens and patients and concluded "we are doing it totally wrong". Some interviewees had prior experience of citizen dialogues when deliberating over new healthcare facilities and said that one must meet and talk to people to gain relevant information. There had been one process of citizen dialogue in the studied project, but the representativeness among the participants was questioned as well as whether the process had reached those in greatest need. A politician argued that overall, they should have done more outreach activities, focus groups and so forth with people, but it was difficult because "there is a lot of bureaucracy in this project now".

It is also relevant to notice that the above description applies to the first phase of the project, 2016-2018. From May 2019 a broader approach to participation has been applied. However, at this stage the frame, concept and scope has been set. A situation that raises issues related to areas from local democracy to co-design not encompassed by this study.

The other aspect of involvement concerned patients in their own care and treatment. It was argued that patients were the only experts of their disease, and another interviewee said that "patients are an underused resource, easy to forget". It was mentioned that the current trend to involve patients as part of the healthcare team for improved quality needed to be more structured and planned. Currently, it was up to each unit/staff to decide how to involve patients and a common way to do it - digital communication - was difficult because these issues were often too complex to explain in writing. In the end it took more time than it saved. Today's information society, were patients are well-informed and have the ability to read up on diagnosis, treatments etc., the requirements, demands and expectations are different than before information and communication technologies became commonplace was a reflection from the interviewees. It was also argued that new legislation would increase patient involvement, for instance when patients were being discharged from hospital, staff from hospital care, primary care and municipality had to jointly plan follow up or continuing home treatment with the patient and their relatives. However, the patients themselves were also variously "good" at getting involved, and often the strong-voiced were prioritized, contributing to a situation described by one of the interviewees; "we often forego those that really are very sick for the benefit of persons that suffer from other reasons".

Collaboration

This dimension is divided into collaboration between traditional healthcare actors and collaboration among actors in the broader

welfare system.

It was commonly assumed that it was a "healthcare-closer-to-people-system" that was supposed to be built. "Today we work as isolated islands", as one interviewee said. A reason to create a system based on the concept "close" was to avoid that patients would travel long distances to seek care at large specialized hospitals. Such a system would enable different competences and functions to be "close" to people. It was argued that geographically, such services could be distributed, but that it needed to be well-established and have smooth ways of working so that the patient "nevertheless perceives some type of closeness". Overcoming organizational boundaries was crucial but a major challenge "because it is different budgets and different traditions and different with everything". Another interviewee added that maybe there was a need to merge the budgets into one and re-organize in order to enable true collaboration.

In the interviews it was argued that better coordination and collaboration were needed and that it would benefit the patient's coherent journey. The different systems for patient records was found to be a barrier, but also the difficulty to just being able call someone at another unit to discuss was a challenge. It was noted in the interviews that it was particularly important to strengthen the existing first-line provider, the primary care to address these issues. More care than today should be provided at primary care level rather than at specialized hospitals, and resources had to be moved from hospitals to primary care, even though this would most likely create a lot of fuss it was noted. Interviewees representing primary care agreed, they also noted that they must be financially compensated more reasonably than today. A comment that implies a challenge to, and questioning of, the internal funding system and principles in the region's healthcare structures.

It was also argued that the future system needed to be bigger than including only the actors from the regional healthcare system. Particularly the municipalities and their care should be included. This was important because municipalities were responsible for care of elderly at home but also health information at schools. Such an expanded system was referred to as a "safety system" or "coherent system". Others argued it was important to delimit the system because they could see no end to such a system to include almost anything, for example national insurance agency and public employment service. Others agreed saying that "systems have a tendency to swell and become very large" and that, besides "pure" healthcare services provided by municipalities and regions, other actors could act as satellites because of their impact on the system and patients" well-being. However, it was argued that these (insurance and employment agencies, for example) could be located at the local healthcare provider once or week. The same would be the case for patient associations. Providing such surfaces for interaction between actors would be important for the new local hospitals.

Discussion

Interconnected dimensions for healthcare closer to people

In this subsection we theorize about the interconnectedness among the three constructed aggregate dimensions and its consequences for providing healthcare closer to people.

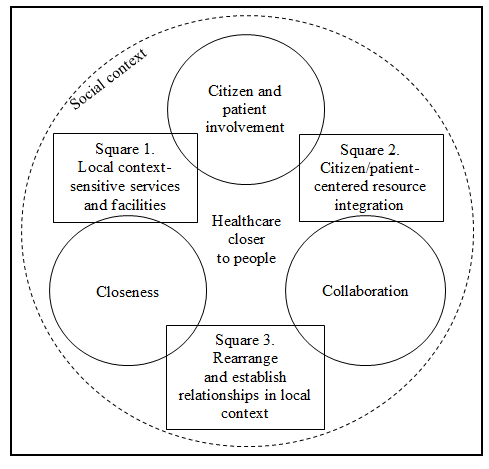

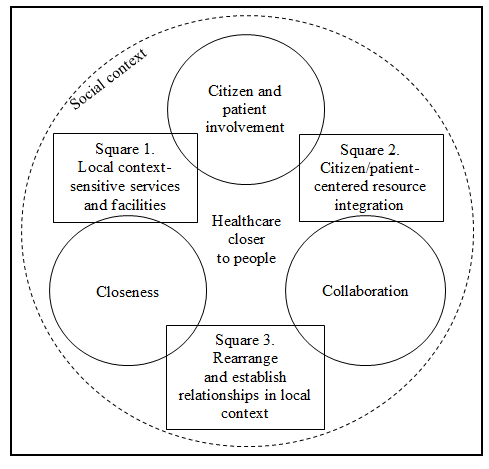

Figure II. The dimensions interconnectedness and embeddedness in social context

Square 1 shows that based on geographical closeness, citizen-focused services could be designed that are relevant for the population in the local context. For example, adapting services and information based on the needs of the population in a specific area - preferably by involving those in developing services and facilities (Jacquez et al., 2013; Olsson et al., 2014). Moreover, citizen-centered closeness could also be provided through digital eHealth services by enabling people to reach particular services despite long distances (Melchiorre, 2018), for example while being on vacation, etc. Closeness and patient-centeredness could also be reached by creating continuity in that patients meet the same staff as often as possible, which in turn would enable relationship-building (Morgan and Yoder, 2012). To sum up, citizen and patient involvement is a prerequisite to create an experience of closeness that also enable knowledge of collectives to be included in designing services (physical or digital), but also on an individual level for the physician or nurse to know how to encounter and interact with a specific patient.

Square 2 addresses the intra-organizational focus of Swedish healthcare, at the expense of issues between organizations (Andersson and Liff, 2012; Fransson and Quist, 2014). This is alarming, not least because many problems are not isolated healthcare, but societal matters of concern (Mintzberg, 2017). For example, the older population require healthcare providers to increase collaborations with other actors than is the case today, for example care provided by the municipalities. By reconfiguring how societal resources are integrated and put together based on the needs of people, new collaborations are likely to emerge, for instance, to provide not separate services, but a joint service through collaboration (Fransson and Quist, 2014; Eriksson et al., 2020). As such, the patient is less likely to fall to the cracks between organizations and their different regulations, borders, budgets, and so forth. Taking a citizen or patient perspective is also a prerequisite for proper collaboration and the only way to visualize the patient's whole journey, rather than the fragments that the separate providers often see and address connected to their delivery (Fransson and Quist, 2014; Morgan and Yoder, 2012).

In square 3, collaboration is sensitive of the local context, for instance through established relationships between staff of regional and municipal care providers that may contribute to a sense of closeness for the patient facing a coherent local system (Fransson and Quist, 2014; Eriksson et al., 2020). Indeed, also specialists from hospitals could visit local providers to keep the local and close attachment. Services do not need to be provided locally but could indeed be provided at other places - but this would require arrangements to be adequately arranged to retain a sense of closeness. With the introduction of a new way to provide care - as the new local hospitals in the present project - knowledge of how primary care, local hospitals, specialized care at large hospitals and municipalities can collaborate must be brought to surface, including patient pathways and facilities needed, logistics/transportation of supplies, usability of the healthcare physical environment, workspaces and patient spaces and intangible resources such as staff's knowledge and skills. The new local hospitals can be a platform for collaboration between the local community and the health needs of the local population - and as such a contributor to social sustainability and accessibility to equal care (Jacquez et al., 2013; Olsson et al., 2014).

Embeddedness in social context

As indicated by the dotted circle in figure II, the reform of moving healthcare closer to people should be understood to be embedded in social context. Something that may help to understand why moving healthcare closer to people is easier said than done.

In the empirical material it is clear that there were tensions between different healthcare actors' perspectives (Mintzberg, 2017) or discourses (Foucault, 1993). It may be argued that due to ways of organizing the public in recent decades (Andersson and Liff, 2012; Fransson and Quist, 2014), management has gained power whereas a depoliticization has occurred in which politicians have lost some of its power (Mattei, 2006) - yet the latter sees themselves as representatives of the people which is manifested in the empirical material as if they either are spokespersons for the people or would like to carry out citizen involvement themselves. A study (Solli, 2017) set in the same regional context as the present case, concluded that interfaces between regional politicians and citizens existed, but that few citizens knew about these gatherings or had little interested in participating in these dialogues at all. Citizen and patient perspective have also been enhanced through the increased importance of deliberative elements of healthcare delivery and design (Culyer and Lomas, 2006), including popular concepts such as person-centeredness (Alharbi et al., 2012; Morgan and Yoder, 2012) as well as underpinned by management discourse in which customer focus from private sector has spilled over on public sector (Andersson and Liff, 2012; Fransson and Quist, 2014). The healthcare professionals impact has been toned down during the management discourse (Doolin, 2002; Malmmose, 2015), but has lately gained increased attention, not least in contemporary Swedish public sector (SOU, 2019b) in which trust in professionals knowledge and skills is highlighted as important (and consequently, a desire to downplay managerial influences) - maybe this is particularly important in healthcare structures in which the medical professions have traditionally have had a strong position. Naturally, other tensions could be brought to surface, for example patient wishes (underpinned by management ideas) versus medical professions' knowledge (Dent, 2006), the digitally enabled patient will also have a better starting point, or negotiating skill, at the same time, calling for research on professional roles - as well as the risk to empower patients as a means to cut costs (Nordgren, 2009).

Conclusion

The current establishment of two local hospitals in a Swedish healthcare context offers a possibility to study aspects of decentralization, more specifically, how healthcare services can be provided closer to people. Three overriding and interconnected dimensions have been highlighted as important to this transformation: closeness, entailing a geographical, accessible, and relational closeness from the citizen's/patient's point of view; citizen/patient involvement, entailing a need to base the starting point from the lived experience of citizens in the local context or patients living with a particular disease in designing "close" services and facilities; and collaboration, entailing that healthcare providers and other actors need to work together to provide citizen-/patient-centered care and a sense of closeness. Moreover, the paper has theorized the importance to recognize the social context in which these dimensions are embedded. Thus, reorientations of healthcare system like this and similar reforms will inevitably bring tensions between logics and discourses to surface. The interconnectedness among the dimensions and the embeddedness in social context are the present paper's theoretical contribution. The contribution to policy is to recognize the multiplicity of actors to increase the likelihood of succeeding with moving healthcare closer to people as well as in managing similar healthcare transformations. Only time will tell whether the Swedish decentralization initiatives are "more rhetorical than real", as questioned in a UK context by Peckham et al. (2008, p. 560). For now, the development around close care and integration between actors is lived experience in a social context. To be experienced

and discussed.

The aspect of decentralization this paper focus is the concept "closeness", citizen/patient involvement as well as collaboration. It is possible that a quantitative or mixed-methods approach would have had highlighted other aspects of decentralization (such as capacity, competence

and so forth).

References

Adam, A., Lindahl, G. and Leiringer, R. (2019), "The dynamic capabilities of public construction clients in the healthcare sector", International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 153-171.

Alharbi, T., Ekman, I., Olsson, L., Dudas, K. and Carlström, E. (2012). "Organizational culture and the implementation of person centered care: results from a change process in Swedish hospital care", Health Policy, Vol. 108 No. 2-3, pp. 294-301.

Alonso, J., Clifton, J. and Díaz-Fuentes, D. (2015), "The impact of new public management on efficiency: an analysis of Madrid's hospitals", Health Policy, Vol. 119 No. 3, pp. 333-340.

Andersson, T. and Liff, R. (2012), "Multiprofessional cooperation and accountability pressures: consequences of a post-new public management concept in a new public management context", Public Management Review, Vol. 14 No. 6, pp. 835-855.

Anell, A., Glenngård, A. and Merkur, S. (2012), Health systems in transition: Sweden. Health System Review 2012. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Copenhagen.

Anton, J, Munoz de Bustillo, R., Fernandez Macias, E. and Rivera, J. (2014), "Effects of health care decentralization in Spain from a citizens' perspective", The European Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 411-431.

Banzon, E. and Mailfert, M. (2018), "Overcoming public sector inefficiencies toward universal health coverage: the case for national health insurance systems in Asia and the Pacific", Asian Development Bank.

Batalden, P. and Davidoff, F. (2007), "What is 'quality improvement' and how can it transform healthcare?", Quality and Safety in Health Care, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 2-3.

Bergman, B., Hellström, A., Lifvergren, S. and Gustavsson, S. (2015), "An emerging science of improvement in health care", Quality Engineering, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 17-34.

Berwick, D. (2008), "The science of improvement", Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 299 No. 10, pp. 1182-1184.

Carmona, S. and Ezzamel, M. (2005), "Making a case for case study research", The Art of Science, Copenhagen Business Press, Copenhagen, pp. 137-152.

Christiansen, T. and Vrangbæk, K. (2018), "Hospital centralization and performance in Denmark - ten years on", Health Policy, Vol. 122 No. 4, pp. 321-328.

Coleman, M., Forman, D. and Bryant, H. (2011), "Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007: an analysis of population-based cancer registry data", The Lancet, Vol. 377 No. 9760, pp. 127-138.

Corley, K. and Gioia, D. (2004), "Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off", Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 49 No. 2, pp. 173-208.

Culyer, A. and Lomas, J. (2006), "Deliberative processes and evidence-informed decision making in healthcare: do they work and how might we know?" Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, Vol. 2 No. 3, pp. 357-371.

Dent, M. (2006),"Patient choice and medicine in health care: responsibilization, governance and proto-professionalization", Public Management Review, Vol. 8 No. 3, pp. 449-462.

Doolin, B. (2002), "Enterprise discourse, professional identity and the organizational control of hospital clinicians", Organization Studies, Vol. 23 No 3, pp. 369-390.

Dubois, H. and Fattore, G. (2009),"Definitions and typologies in public administration research: the case of decentralization", International Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 32 No. 8, pp. 704-727.

Eriksson, E., Andersson, T., Hellström, A., Gadolin, C. and Lifvergren, S. (2020),"Collaborative public management: coordinated value propositions among public service organizations", Public Management Review, Vol. 22 No. 6, pp. 791-812.

Ferrario, C. and Zanardi, A. (2011), "Fiscal decentralization in the Italian NHS: what happens to interregional redistribution", Health Policy, Vol. 100 No. 1, pp. 71-80.

Foucault, M. (1993), Diskursens ordning [The order of discourse], Brutus Östlings Symposium, Stockholm.

Fransson, M. and Quist, J. (2014), Tjänstelogik för offentlig förvaltning [Service logic for public administration], Liber, Stockholm.

Gatta, G., Capocaccia, R. and Botta, L. (2017), "Burden and centralised treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet-a population-based study", The Lancet Oncology, Vol. 18 No. 8, pp. 1022-1039.

Gauld R. New Zealand's post-2008 health system reforms: toward re-centralization of organizational arrangements. Health Policy 2012;106(2):110-3.

Gaventa, J. and Cornwall, A. (2007), "Power and knowledge", in Bradbury, H. and Reason, P. (Eds), The Sage Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, Sage, London, pp. 172-189.

Gioia, D., Corley, K. and Hamilton, A. (2013),"Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the Gioia methodology", Organizational Research Methods, Vol. 16 No. 1, pp. 15-31.

Greenwood, D. and Levin, M. (2007), Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change, Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Heaney, D., Black, C., O'Donnell, C., Stark, C. and Van Teijlingen, E. (2006), "Community hospitals - the place of local service provision in a modernising NHS: an integrative thematic literature review", BMC Public Health, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 309-320.

Jacquez, F., Vaughn, L. and Wagner, E. (2013), "Youth as partners, participants or passive recipients: a review of children and adolescents in community-based participatory research (CBPR)", American Journal of Community Psychology, Vol. 51 No. 1-2, pp. 176-189.

Learn, P. and Bach, P. (2010), "A decade of mortality reductions in major oncologic surgery: the impact of centralization and quality improvement", Medical Care, Vol. 48 No. 12, pp. 1041-1049.

Lincoln, Y. and Guba, E. (1985), Naturalistic Inquiry, Sage, Newbury Park.

MacDorman, M., Mathews, T., Mohangoo, A. and Zeitlin, J. (2014), "International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010", National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol. 63 No. 5, pp. 1-7.

Madon, S., Krishna, S. and Michael, E. (2010), "Health information systems, decentralisation and democratic accountability", Public Administration and Development, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 247-260.

Magnussen, J., Hagen, T. and Kaarboe, O. (2007), "Centralized or decentralized? A case study of Norwegian hospital reform", Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 64 No. 10, pp. 2129-2137.

Malmmose, M. (2015), "Management accounting versus medical profession discourse: hegemony in a public health care debate- a case from Denmark", Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 144-159.

Mattei, P. (2006), "The enterprise formula, new public management and the Italian health care system: remedy or contagion?", Public Administration, Vol. 84 No. 4, pp. 1007-1027.

Mauro, M., Maresso, A. and Guglielmo, A. (2017), "Health decentralization at a dead-end: towards new recovery plans for Italian hospitals", Health Policy, Vol. 121 No. 6, pp. 582-587.

Melchiorre, M., Papa, R., Rijken, M., van Ginneken, E., Hujala, A. and Barbabella, F. (2018), "E-health in integrated care programs for people with multimorbidity in Europe: insights from the ICARE4EU project", Health Policy, Vol. 122 No. 1, pp. 53-63.

Mintzberg, H. (2017), Managing the Myths of Health Care: Bridging the Separations Between Care, Cure, Control, and Community, Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Morgan, D. (1996), "Focus groups", Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 22 No. 1, pp. 129-152.

Morgan, S. and Yoder, L. (2012), "A concept analysis of person-centered care", Journal of Holistic Nursing, Vol. 30 No. 1, pp. 6-15.

Nordgren, L. (2009), "Value creation in health care services-developing service productivity: experiences from Sweden", International Journal of Public Sector Management, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 114-127.

Olsson, E., Lau, M., Lifvergren, S. and Chakhunashvili, A. (2014). "Community collaboration to increase foreign-born women s participation in a cervical cancer screening program in Sweden: a quality improvement project", International Journal for Equity in Health, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 62-72.

Osborne, D. and Gaebler, T. (1992), Reinventing Government: How the Entrepreneurial Spirit is Transforming the Public Sector. Addison-Wesley, Reading.

Osborne, S. (2018), "From public service-dominant logic to public service logic: are public service organizations capable of co-production and value co-creation?", Public Management Review, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 225-231.

Park, S., Lee, J., Ikai, H., Otsubo, T. and Imanaka, Y. (2013), "Decentralization and centralization of healthcare resources: investigating the associations of hospital competition and number of cardiologists per hospital with mortality and resource utilization in Japan", Health Policy, Vol. 113 No. 1, pp. 100-109.

Peckham, S., Exworthy, M., Powell, M. and Greener, I. (2008), "Decentralizing health services in the UK: a new conceptual framework", Public Administration, Vol. 86 No. 2, pp. 559-580.

Pettersen, I. (2001), "Hesitation and rapid action: the new public management reforms in the Norwegian hospital sector", Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 17 No. 1, pp. 19-39.

Pollitt, C. (2005),"Decentralization: a central concept in contemporary public management", in Ferlie, E., Lynn, L. and C. Pollitt (Eds), The Oxford Handbook of Public Management, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 371-397.

Ragin, C. and Becker, H. (1992), What is a Case?: Exploring the Foundations of Social Inquiry, Cambridge university press, Cambridge.

Saltman, R. (2008), "Decentralization, re-centralization and future European health policy", European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 18 No. 2, pp. 104-106.

Saltman, R., Busse, R. and Figueras, J. (2006), Decentralization in Healthcare: Strategies and Outcomes, McGraw-Hill Education, New York.

SFS (2017), Hälso- och sjukvårdslag, Nordstedts, Stockholm.

SKR (2018), Svensk sjukvård i internationell jämförelse, SKR, Stockholm.

SKR (2019a), Hälso- och sjukvården år 2035.

SKR (2019b), Framtidens vårdbyggnader.

SKR (2020), Presentation 2020-01-22, Association of Swedish Municipalities and Regions, SKR, Annual assembly of the Network of real estate and asset managers.

Socialstyrelsen (2003), Kartläggning av närsjukvård 2003, Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm.

Socialstyrelsen (2013), Tillståndet och utvecklingen inom hälso- och sjukvård och socialtjänst, lägesrapport 2013, Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm.

Solli, R. (2017), Utvärdering av Västra Götalandsregionens politiska organisation, 2017.

Statistics Sweden (2019), Befolkningens sammansättning.

SOU (2016), Effektiv vård, Elanders, Stockholm.

SOU (2019a), God och nära vård, Elanders, Stockholm.

SOU (2019b), Med tillit följer bättre resultat, Elanders, Stockholm.

Vårdanalys (2014), Vården ur patienternas perspektiv, TMG, Stockholm.

Versteeg, S., Ho, V., Siesling, S. and Varkevisser, M. (2018), "Centralisation of cancer surgery and the impact on patients' travel burden", Health Policy, Vol. 122 No. 9, pp. 1028-1034.

VGR (2017), "Strategi för hälso- och sjukvårdens omställning i Västra Götalandsregionen 2017.

Weitz, J., Koch, M., Friess, H. and Büchler, M. (2004), "Impact of volume and specialization for cancer surgery", Digestive Surgery, Vol. 21 No. 4, pp. 253-261.

Wouters, M., Karim-Kos, H. and le Cessie, S. (2009), "Centralization of esophageal cancer surgery: does it improve clinical outcome?", Annals of Surgical Oncology, Vol. 16 No. 7, pp. 1789-1798.

Send by e-mail: