Publications IPH Magazine Magazine IPH Nº19 Jarbas Karmans experience during his SESP Years

- Editorial Magazine IPH Nº19

- From Hospital Architecture to Architecture for Health

- Design for health environments: how neuroscience applied to architecture can contribute to the health and well-being of its users

- Jarbas Karmans experience during his SESP Years

- Evolution of hospital building, its alignment with medical sciences and patient care in the city of São Paulo

This article aims to approximate the architectural production of Jarbas Karman during the period he worked for SESP ? Special Public Health Service

SESP was created in 1942 with the aim of sanitizing territories that produced raw material, in addition to training professionals through exchange programs.

Karman worked at the institution between 1949 and 1951, where he was responsible, among other roles, for the project of Maternidade Escola de Belém (1949) and Marabá?s hospital on stilts (1950).

The experience at SESP was of great importance for Karman?s professional training. It allowed him to have direct contact with deep Brazil?s reality and understand hospital buildings needed more attention when planned and managed.

Keywords

jarbas karman, sESP, architecture, hospitalcenters.

1. Introduction

The architecture of hospitals has changed intensely throughout the 20th century in Brazil. Taking into account the writings of Lauro Miquelin (1992), Luiz Carlos Toledo (2006), Renato da Gama-Rosa Costa (2011), Ana Amora Albano (2014), Elza Costeira (2014) and Antônio Pedro Alves de Carvalho (2014), researchers dedicated to researching this topic, it can be said that the architecture of hospitals underwent three paradigmatic changes: first, the adoption of the 19th-century French pavilion model as the best design and construction solution (between the 1900s and 1930s); second, the verticalization of buildings, initially inspired by the American experiences at the turn of the century and, later, by European modernism, mainly in the architecture of Le Corbusier (between the 1930s and 1950s); third, the criticism and rupture with pre-established models, resuming some of the ideas of the 19th century, valuing the well-being of patients and incorporating the most advanced administrative and operational practices at the time.

This third paradigm shift had as one of its protagonists architect Jarbas Karman, who dedicated 59 years of his career to designing, researching and teaching in the area of architecture, engineering and administration of hospital institutions

His trajectory begins at SESP ? Special Public Health Service, an arm of the Brazilian government that had as one of its objectives carrying out equipment and infrastructure works in the health area. Karman worked for about a year at the institution, but this experience was fundamental for his professional training.

The purpose of this article is to carry out an analysis of some of the experiences of the architect Jarbas Karman during this period.

2. Jarbas Karman: an architect in search of knowledge

Born in the city of Campanha, in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, Jarbas Bela Karman became interested in hospital planning during his specialization as an architect. First, he graduated in Civil Engineering, in 1941, from the Polytechnic School of the University of São Paulo ? Poli USP. During his graduation, he attended CPOR (Reserve Officers Training Center), becoming a second lieutenant in the Army reserve. With a double title ? lieutenant and engineer ? he served the Brazilian Army during the Second World War, in 1942, in northern Brazil, collaborating with the construction of fortifications.

In the early 1940s, in the state of São Paulo ? where Karman lived most of his life ? architecture schools were still part of engineering courses. The first one to become independent was School of Architecture of Mackenzie University, in 1947, and, a year later, the School of Architecture and Urbanism of the University of São Paulo ? FAU USP. Before that, architect training used to take place as an extension of the civil engineering course.

After serving the Army, Karman studied architecture, graduating in 1944, also from Poli USP. During his specialization, he became interested in the planning of hospitals, because, according to Karman himself, he could not get answers to the doubts that arose during the design workshop he took on the subject, which at the time was mandatory for the education of an architect.

In 1949, following his desire to work in the field of public health, he was admitted to the Special Public Health Service (SESP). The position consisted of developing and supervising construction projects, renovations and adaptations of health institutions for the riverside population in the Amazon Valley and in the São Francisco River Valley

Karman worked at SESP for about a year. He moved with his wife to Belém do Pará and started to develop projects for hospitals and health centers in several Brazilian cities.

The testimonies and manuscripts from his collection indicate that the experience at SESP was fundamental for his education. By having contact with the riverside population and with villages that did not have basic sanitation and health education, in addition to scarce resources to build, renovate or update healthcare units, he understood architecture should, in order to achieve good results in the area of public health, team up with hospital management, besides, obviously, understanding local social, cultural, economic and geographic issues in order to apply resources in the best possible way.

SESP was created based on a partnership between Brazil and the USA (an issue that will be dealt with later). The partnership provided for the granting of scholarships and funding for the training of professionals abroad. Knowing this, Karman applied for a scholarship to pursue a Masters in Hospital Architecture at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The fellowship was awarded, and he left for North America in 1951.

His experience abroad was quite extensive: he traveled across Canada and dozens of US cities. He attended courses on operating theaters and sterilization centers in Ontario, hospital planning in New York, and hospital safety in Boston.

After completing his master?s degree, in 1952, he returned to Brazil and established his architecture office in the city of São Paulo and started a campaign to disseminate the knowledge he acquired during his experience at SESP and his studies in North America.

Throughout his career, the architect collaborated with dozens of undergraduate and graduate courses; participated in conferences, congresses and seminars and gave classes and lectures in Brazil and abroad; published more than a hundred articles in national and international journals and wrote three books: ?Iniciação à Arquitetura Hospitalar? (1972), ?Manual de manutenção hospitalar? (1994) e ?Manutenção e segurança hospitalar preditivas? (2011 ? released posthumously) , in addition to participating as organizer and author of the publication ?Planejamento de Hospitais? (1954). He was a member of several institutions dedicated to the hospital area, including abroad, among which the ?Public Health Group of the International Union of Architects? (UIA-PHG) and ?The American Public Health Association? stand out; he participated in several commissions for the elaboration of resolutions and technical standards of institutions such as ANVISA and ABNT. Under the command of his office, he developed more than 300 architectural projects for healthcare buildings, including new constructions, renovations, expansions and reformulations of different scales and programs.

He died in São Paulo, on June 2, 2008.

In an article written for IPH Magazine, in 2004, Karman states SESP had the merit of being his ?preparatory Brazilian internship? for his training in North America and for the creation of IPH (Karman, 2004, p. 7). In order to contribute to research on the transformations of Brazilian hospitals and to document Jarbas Karman?s work, it is necessary to better understand the actions of this service linked to the Brazilian government and the role of the architect as a collaborator.

3. Architects of SESP

Shortly before the end of World War II, with the intensification of relations with the Soviet Union, Americans created an international cooperation program between allied nations, with the aim of strengthening political and economic relations, which became known as Ponto IV. Brazil was one of the countries that received funds from this program, aimed at technicalscientific development in several areas, including the sanitary field.

One of the consequences of this cooperation was the creation of the Special Public Health Service ? SESP. Configured as a bilateral agency, it was created by the Brazilian government with resources and under the guidelines of the US government after the Third Meeting of Consultation with the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of the American Republics, in 1942

The main objectives of SESP were to promote basic sanitation in the regions responsible for the production of strategic raw materials for war, such as rubber, iron ore and mica (Adriano; Pessoa, 2017). It was necessary to improve the health of workers in the Amazon regions and in Rio Doce Valley.

Researcher Lina Rodrigues Faria states that:

Since the 16th century, various diseases such as malaria, smallpox, measles, hookworm, dysentery and yellow fever affected a large part of the free and slave population in Brazil?. (Faria, 2006).

Faria emphasizes in her text that malaria was the most significant case, given that in the Amazon region there were ?vast areas endemic to the disease?. The riverside populations of the São Francisco and Rio Doce valleys were two of those who suffered most from the devastating action of the disease.

To contribute to the basic sanitation of these regions, SESP hired architects to develop projects for the construction and renovation of health units. A fact of great importance in the country, considering that the participation of architects in the sector would only be intensified from the second half of the 20th century.

Professor and researcher Antônio Pedro Alves de Carvalho, in an article on Brazilian norms for the design and construction of hospitals, highlights the participation of SESP in this process:

SESP worked in several rural health and sanitation programs until its extinction in 1990. One of the great advances of this service, at the time, was the training of specialists in courses in the United States. This exchange of knowledge also encompassed architecture, with the creation of the hospital architecture section? (CARVALHO, 2017, p. 22).

One of the consequences of the work of architects at SESP was the creation of the Minimum Hospital Standards (BRASIL, 194?), a guide with technical guidelines for the design of small and medium-sized general hospitals. Written by architects Roberto Nadalutti and Oscar Valdetaro3, the publication has texts, architectural plans and detailed lists of furniture and equipment. Carvalho points out that this guide ?can be considered the basis of all legislation in the area of healthcare architecture in Brazil? (Carvalho, 2017, p.24).

As mentioned above, the exchange of professionals between Brazil and the United States is another important factor to understand SESP?s contributions to the transformation of hospital buildings. Karman, Nadalutti and Valdetaro benefited from scholarships to study in North America. According to architect and professor Luiz Carlos Toledo, in addition to Karman?s master?s degree at Yale, the three architects took a specialization course offered by the Public Health Service, Division of hospitals Facilities, in 1952, in the USA (Toledo, 2020, p.38).

The production of these architects in this period is still very little known.

There is no further information about his projects and accomplishments.

Considering the importance Karman himself attributes to SESP in his formation, it is important to know better his production prior to his master?s degree in the USA.

4. Two hospitals designed bby Karman for SESP

Jarbas Karman Collection, which is part of IPH Collection, shows that the architect developed at least ten projects for healthcare buildings while he worked for SESP, in cities located in the states of Pará, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Bahia and Minas Gerais.

There are not drawings of all the projects in the collection, which prevents deeper research into their production before their trip to North America. However, the architect managed to preserve drawings of two projects from that period, which will be presented below.

4.1. Belém Maternity Shcool

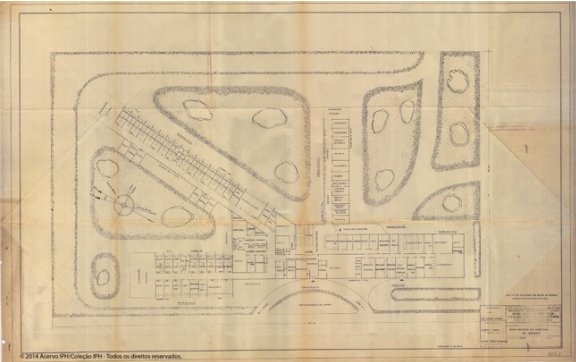

The first hospital designed by Karman was Maternidade Escola de Belém do Pará, in 1949. Of considerable monumentality for the region, the building would occupy approximately one third of the block formed by José Bonifácio avenue, Gentil Bitencourt avenue, Deodoro de Mendonça street and Farias de Brito street.

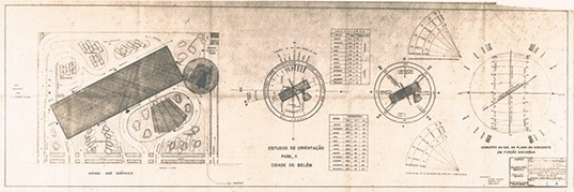

The lot was reserved, at the time, for the construction of Belém City Arena. As you can see on the layout plan (illustration 1), the project consists of a six-story blade located on the northeast-southwest diagonal of the lot, connected by a walkway to a trapezoidal-shaped volume equivalent to four floors in height.

The building was not carried out as proposed on Karman?s ideas. In a recent survey, developed by Aristóteles Guilliod de Miranda, from the School of Architecture and Urbanism of the Federal University of Pará and published on the Virtual Laboratory website ? FAU ITEC UFPA (2015), there were significant changes in the original project. The justification was that it was necessary to adapt the proposal to current legislation. Sometime later, it was destined to house Augusto Meira School, undergoing a drastic change of use. The built project retains few traces of the original. The implantation was adjusted to the north-south axis and other volumes were added. From Karman ?s drawing, only the relationship between the blade and the trapezoidal volume of the auditorium4 remains.

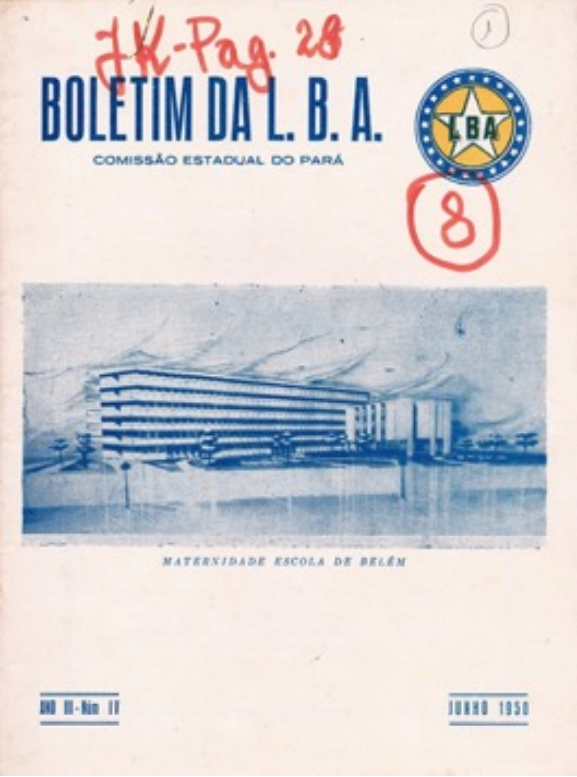

The project was the cover of issue IV, year III, of the Bulletin of the LBA (Legião Brasileira de Assistência) ? State Commission of Pará ? in June 1950

4.2. Hospital in Marabá

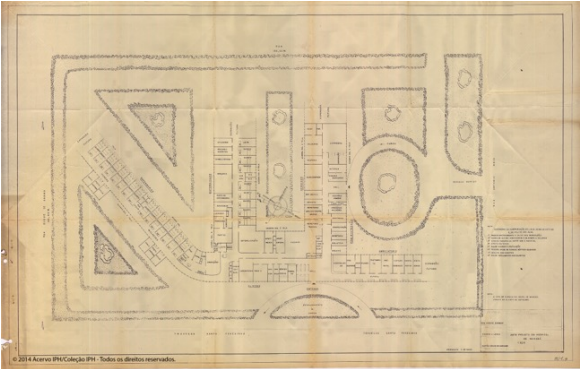

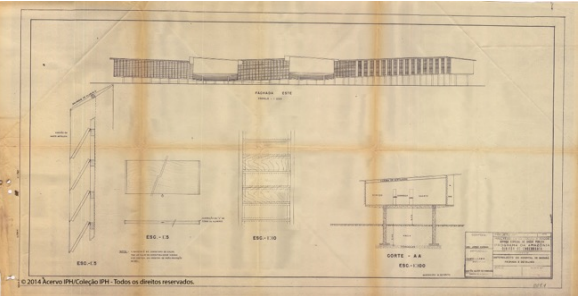

There are two versions of the project. One dated from May 30, 1950, and one undated. Both versions have a single floor suspended from the ground by concrete pillars.

The undated one, which will be called the first version from now forward, has two boards: one with the general plan of the hospital implanted in the lot, in scale 1:200; another with a schematic section, an elevation and constructive details, in varied scales.

When observing the elevation, it is possible to notice that the project proposed an inclined floor, defined by him as ?wing slope?, that is, with a ramped floor in the entire extension of the pavilions, with height variation between 1.50 m (in the accesses) and 4.00 m (at the end of the pavilions) from the ground.

2° Gain in height with the economy of ramps and columns

3° Use of the part under the hospital

4° Aesthetic effect

5° Greater hygiene and ventilation

6° Possibility of raised septic tank

7° Slopes leading to sewers

8° Greater isolation of rooms (Karman, 1950).

The schematic section and detail of brises show Karman ?s concern for the local climate. The project proposes larger eaves for the faces with greater insolation, a ventilated space between the roof and the lining and louvers in aluminum and wood, a furniture that would allow patients to control the amount of natural light in the rooms.

The dated plank, which in this article is referred to as the second version, is also composed of four interconnected pavilions, three of which are orthogonal and one diagonally in relation to the streets. Also capable of holding 40 beds, it has a more elaborate program, with three accesses instead of two, one for employees and general services, one for emergencies (facing Travessa Santa Teresinha) and another for the outpatient clinic (facing to Antônio Maia Street). The accesses are ramped, which indicates that this proposal maintains the idea of raising the hospital from the ground.

It was not possible to verify whether the second version maintained the proposed slope of the ground floor slab, as was thought for the other version.

Considering the changes in the organization and positioning of the operating room and the obstetrics center, and that these changes would be improved in later projects, it is possible to say that the second version is the most recent, and the architect developed it to improve the project.

Currently there is a hospital built on the site, called Hospital Materno Infantil de Marabá. The implantation of the set does not correspond to either of the two versions developed by Karman, however the characteristics of the external closures (modulation of the frames), the use of apparent roofs and, mainly, the suspension of the ground floor in relation to the ground by pilotis suggest that the architect?s ideas served as the basis for the construction of the hospital.

5. Final considerations

The formal boldness of the project for Belém and the lightness of the architectural complex suspended by stilts, added to the organizational issues of the second version of the project for Marabá, are indications that Karman no longer agreed with the common practices of the early 20th century and that he was already trying to the break with pre-established models, returning to valuing the well-being of patients and suggesting new architectural arrangements to make institutions more efficient and safe.

His experience at SESP was significant to the point that he was released from the obligation to develop a master?s graduation work, whose theme was the design of a general hospital. Researcher Monica Cytrynowicz, writing about the origins of IPH, reveals that Karman ?s advisor at Yale, prof. Bouis, allowed him, as he had already designed and built hospitals of considerable size, to dedicate himself only to research and theoretical studies on the subject (CYTRYNOWICZ, 2014, p.23)

Faced with these facts, not only in relation to Karman?s projects, but also the publication of the first guide to the design and construction of hospitals by Nadalutti and Valdetaro, it is evident that the production of SESP architects has made a great contribution to the transformation of Brazilian healthcare buildings. Nonetheless, this subject needs further documentation and further research.

Bibliography and references

Livros

AQUINO, Paulo Mauro Mayer de; COSTA, Ana Beatriz Bueno Ferraz; VICENTE, Erick Rodrigo da Silva. O desenho de hospitais de Jarbas Karman: exposição realizada durante o VII Congresso Brasileiro para o Desenvolvimento do Edifício Hospitalar. São Paulo: IPH, 2017.

CARVALHO, Antonio Pedro Alves. Introdução à arquitetura hospitalar. Salvador, BA: UFBA, FA, GEA-hosp, 2014.

COSTA, Renato Gama-Rosa. Arquitetura hospitalar em São Paulo. In: MOTT, Maria Lúcia; SANGLARD, Gisele (Org.). História da saúde: São Paulo: instituições e patrimônio histórico e arquitetônico (1808-1958). Barueri, SP: Minha Editora, 2011. p. 25-61.

COSTEIRA, Elza. Reflexões sobre a edificação hospitalar: um olhar sobre a moderna arquitetura de saúde no Brasil. In: Bitencourt, Fábio; Costeira, Elza (org). Arquitetura e engenharia hospitalar. Rio de Janeiro: Rio Books, 2014. p. 101-140.

CYTRYNOWICZ, Monica Musatti. Instituto de pesquisas hospitalares arquiteto Jarbas Karman ? IPH: 60 anos de história. São Paulo: Narrativa Um, 2014.

KARMAN, Jarbas B.; LEVI, Rino; PRADO, Amador Cintra do. Planejamento de Hospitais. São Paulo: IAB-SP, 1954.

MIQUELIN, Lauro Carlos. Anatomia dos edifícios hospitalares. São Paulo: Cedas, 1992.